The Supreme Court heard oral argument in two cases on Wednesday, which wrapped up the arguments for November. I’m predicting the winners of the Supreme Court cases based on the number of questions asked during oral argument. For more about this method, see my post on last Term’s Aereo case.

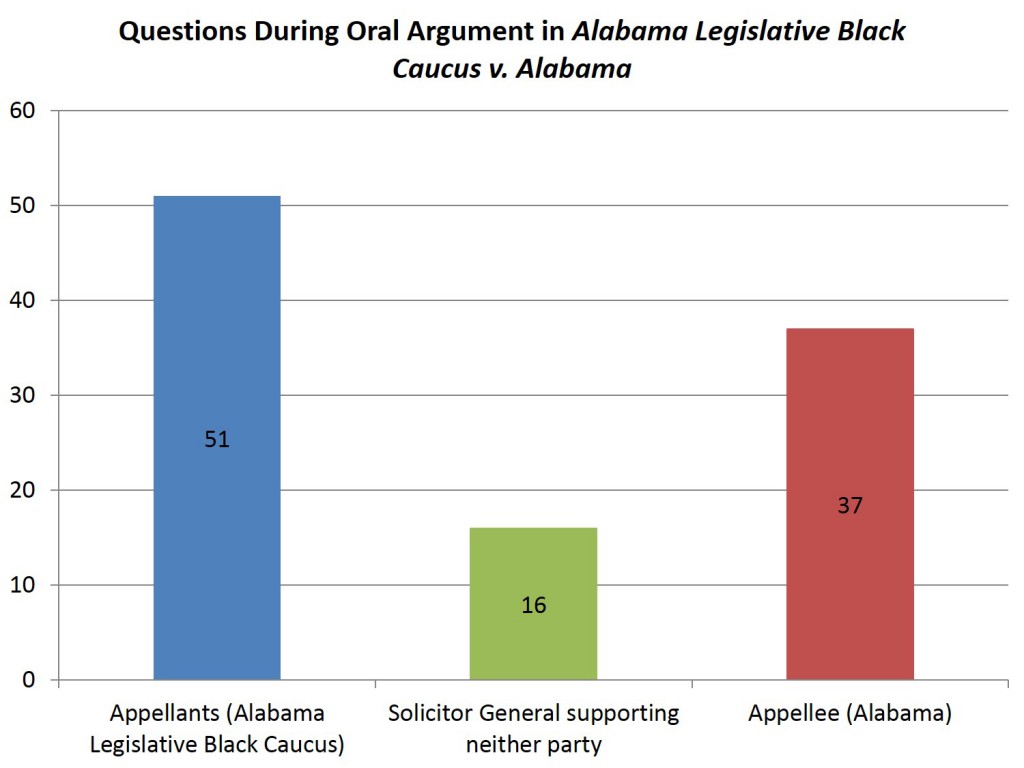

Alabama Legislative Black Caucus v. Alabama asks whether Alabama’s legislative redistricting plans unconstitutionally classify black voters by race by intentionally packing them in districts designed to maintain supermajority percentages produced when 2010 census data are applied to the 2001 majority-black districts.

This case is difficult to predict because of the participation of the Solicitor General supporting neither party. By my count, the Court asked the Appellants 51 questions, a fairly high number and 14 more than the Appellee, who was asked 37 questions. The number of questions to the Appellants might be inflated by the fact that 2 attorneys argued (separately) for that side (some Justices seemed to pepper both attorneys with questions). The Court asked the Solicitor General 16 questions during 10 minutes. Without the SG, the question count points to a victory for the Appellee (Alabama), given the large disparity of questions asked (14 more to the Appellant).

So the question is: will the Court favor the SG’s view (finding error in the district court’s decision upholding Alabama’s redistricting) or Alabama’s view (arguing for affirmance of the district court’s decision)?

The question count does not tell us much to answer this question, given the SG’s 10 minutes versus Alabama’s 30 minutes of questioning. What is apparent is that the decision is likely to break down along conservative and liberal lines.

Three conservative Justices (Roberts, Scalia, Alito) asked the Appellee (Alabama) fewer questions (8, 9, and 1 fewer, respectively), and three liberal Justices (Ginsburg, Breyer, Kagan) asked the Appellants (Alabama Legislative Black Caucus) fewer questions (2, 2, and 9 fewer, respectively). Interestingly, Justice Sotomayor, unlike the three aforementioned liberal Justices, asked far more questions (10) to the Appellant, but none to the SG or Appellee. Meanwhile, Justice Kennedy, unlike the three aforementioned conservative Justices, asked one more question to the Appellee.

I don’t have much confidence predicting the decision based on these numbers. But, if I had to choose, my guess would be 5-4 decision for affirmance. I am swayed by the large disparity in the number of questions asked to the two sides, a number that suggests a win for the Appellee (Alabama), which was asked far fewer questions.

Figure 1.

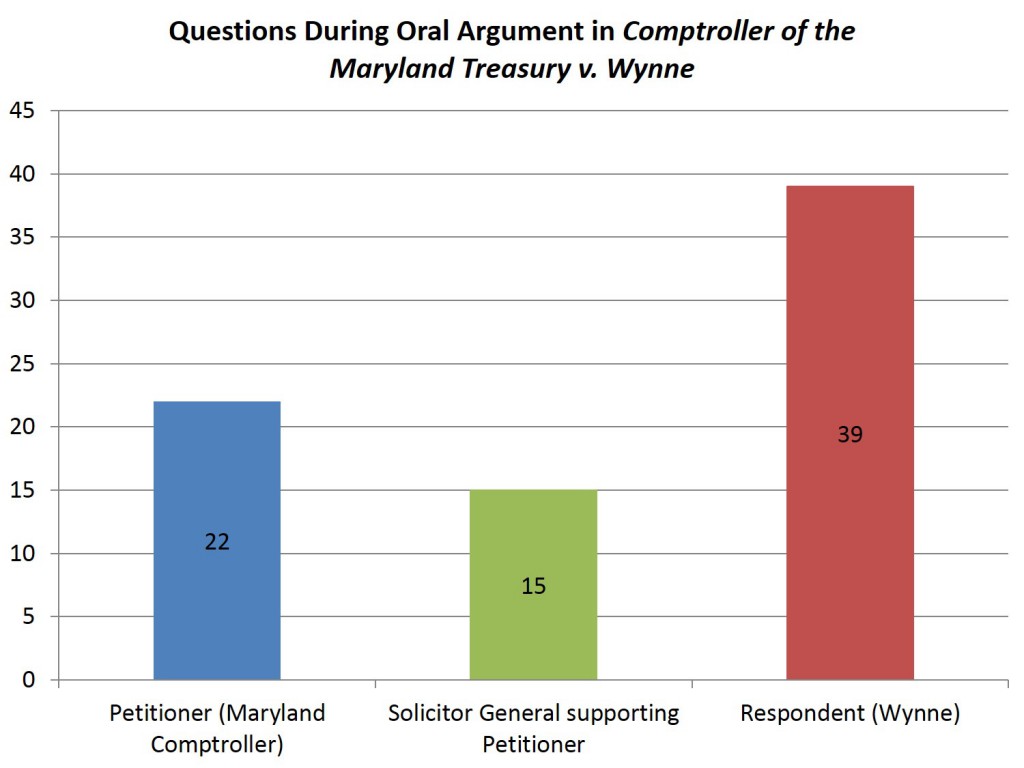

The second case, Comptroller of the Maryland Treasury v. Wynne, asks whether the United States Constitution prohibits a state from taxing all the income of its residents—wherever earned–by mandating a credit for taxes paid on income earned in other states.

This case is a close call. The Court asked the Petitioner (Maryland Comptroller) 22 questions, the Solicitor General supporting Petitioner 15 questions, and the Respondent (Wynne) 39 questions. Thus, by side, the Court asked close to the same number of questions: 37 questions to the Petitioner’s side and 39 questions to the Respondent’s side.

The Justices again appear to be divided along conservative-liberal lines. Three conservative Justices (Roberts, Scalia, Alito) asked the Respondent fewer questions than the Petitioner (3, 5, and 1 fewer, respectively). Four liberal Justices (Ginsburg, Breyer, Sotomayor, Kagan) asked the Petitioner fewer questions (10, 5, 3, and 8 fewer, respectively). Justice Kennedy appears to be the swing vote. But he asked three questions to both the Petitioner and the Respondent, plus three to the SG. What also must be taken into account is that prior studies have found the pattern of question count less accurate for Justice Kennedy.

Based on the question count, I see another 5-4 decision. But which way? Whichever way Justice Kennedy goes. If I had to make a guess, I would pick a win for the Respondent (Wynne) based on the surmise that Justice Kennedy ends up going with the other conservative Justices, who seem to be favoring the Respondent’s argument.

Figure 2.