On this day in 1811, the Senate confirmed, by voice vote, two of President James Madison’s nominees to the Supreme Court, Joseph Story and Gabriel Duvall.

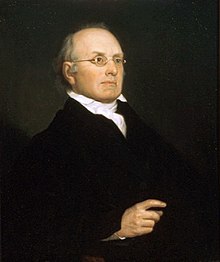

[Joseph Story]

At 32, Story was the youngest Supreme Court appointee in history. The two men received their commissions that same day. (Once they arrived at the Court, Duvall who was 58 years old, was given seniority over Story because he was older.) Duvall, who served as Chief Justice of the Maryland General Court from 1796 to 1802 and as Comptroller of the Treasury under Madison, took the seat of Justice Samuel Chase, a fellow Marylander, who had died the previous June. Story replaced Justice William Cushing, who had died over a year earlier. Both Story and Cushing hailed from Massachusetts.

Earlier in 1811, Madison tried three separate times to fill Cushing’s seat. Levi Lincoln was appointed and commissioned, but declined the nomination because of failing eyesight. The Senate rejected customs inspector Alexander Wolcott by a 9-24 vote, largely because of Wolcott’s public support and enforcement of the Embargo Act of 1807. The Senate then unanimously confirmed John Quincy Adams, but he declined the honor.

At the time of his nomination, Story had already argued a case, Fletcher v. Peck, before the Court. He had a successful law practice through which he was earning $5,000 to $6,000 per year. His acceptance of the position on the Court meant he had to take a pay cut to $3,500. After taking his seat on the Court, Story wrote a friend to explain his decision. He cited the “high honor” of a serving on the Supreme Court, “the permanence of the tenure, the respectability, if I may so say, of the salary, and the opportunity it will allow me to pursue, what of all things I admire, judicial studies, have combined to urge me to accept.”

The two justices who joined the Court together left very different marks on the institution. Justice Duvall had a rather undistinguished career on the Court; he served until his retirement in 1835. Justice Story, who served until his death on September 10, 1845, wrote many significant opinions as well as influential multi-volume commentaries on the law. He has gone down in history as one of the most important justices in the history of the Court, second only to the great Chief Justice John Marshall during the Court’s first half-century.

This post was drafted by ISCOTUS Fellow Bridget Flynn, Chicago-Kent Class of 2019, and edited by ISCOTUS Editorial Coordinator Anna Jirschele, Chicago-Kent Class of 2018, and ISCOTUS Co-Director Professor Christopher Schmidt.