Trump v. Hawaii, the challenge to the third version of the travel ban issued by President Trump, was the last argument of the Term, argued on April 25. The case featured two extremely experienced advocates: former Acting Solicitor General for the Obama Administration, Neal Katyal, representing the state of Hawaii, and current Solicitor General, Noel Francisco.

In a proclamation, President Trump limited travel from eight countries: Chad, Libya, North Korea, Iran, Somalia, Syria, Venezuela, and Yemen. Hawaii challenged the proclamation, arguing that it exceeded the president’s authority under the Immigration and Nationality Act (“INA”), specifically section 1182(f), and also violated the Constitution. The federal district court issued a preliminary injunction blocking the order and the Ninth Circuit upheld that ruling. The courts held that the proclamation likely violates the Immigration and Nationality Act.

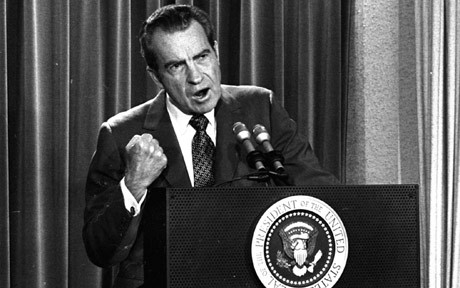

The government defended the proclamation as within the President’s INA authority because the statute gives the president a “broad and flexible power,” and the proclamation reflects his foreign policy and national security judgment as to whether the government has enough information needed to determine whether aliens from particular countries are admissible. The government also argued that under the 1972 case, Kleindienst v. Mandel, once the government presents a legitimate reason, such as national security, for not admitting aliens, the decision is not subject to judicial review.

Addressing the statutory argument, Katyal argued that Congress already implemented a three-part plan to address the problem of certain countries not providing sufficient information for the U.S. government to vet nationals, and that plan included a ban on nationality discrimination in section 1152, also part of the INA.

The advocates also addressed whether the proclamation violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment because an objective observer would conclude that it was adopted for the purpose of excluding Muslims. In a high-stakes concession, Katyal agreed with Chief Justice Roberts that if the President “tomorrow” disavowed any anti-Muslim purpose or rhetoric, the Establishment Clause issue would disappear. In apparent response, in the last 30 seconds of his rebuttal, Solicitor General Francisco stated:

Well, the President has made crystal-clear on September 25 that he had no intention of imposing the Muslim ban. He has made crystal-clear that Muslims in this country are great Americans and there are many, many Muslim countries who love this country, and he has praised Islam as one of the great countries of the world. This proclamation is about what it says it’s about: Foreign policy and national security.

This statement turned out to be one of the most controversial in the case. Observers tried unsuccessfully to identify what September 25 statement the Solicitor General was referring to. (Full disclosure: I am one of many who said publicly that it was important for the government to correct or clarify the statement.) On May 1, the government filed a letter correcting the date in question, indicating that the reference was to January 25, 2017, and statements made that day that were cited in its reply brief. This clarification has not satisfied opponents of the proclamation. Since oral argument, and despite Katyal’s concession, the President and his press secretary have declined to make any disavowals of an intent to ban Muslims.

Bridget Flynn, Chicago-Kent Class of 2019, contributed this post.