When it comes to the role of the Supreme Court on the presidential campaign trail, how does the 2016 election compare to past elections? For all its precedent-shattering and unpredictable qualities, the 2016 campaign basically fell into a predictable dynamic when it came to the candidates’ treatment of the Court.

As I discussed in my earlier posts in this series on the Court and the 2016 election, although the future of the Court played a major role in the election for many voters and for advocacy groups, the candidates themselves showed relatively little interest in the issue. This limited interest only decreased as Election Day approached. In my last post, I offered factors that help explain why neither Trump nor Clinton demonstrated much interest in making the future of the Court a central campaign issue. In this post, I turn to history to show that the Court has always been a difficult issue on the campaign trail for presidential candidates.

The presidential candidates’ relative lack of engagement with the Supreme Court fits a general historical pattern. One of the lessons of history is that presidential candidates rarely find enough advantage in discussing the Court to make it a central issue of their election campaigns. For presidential candidates, the Supreme Court has always been an unwieldy and risky campaign issue.

For much of American history, presidential candidates believed that the Supreme Court was not an appropriate campaign issue or that the American people would disapprove of making a political issue of the Court. They therefore consciously avoided making the Court an issue on the campaign trail. The 1860 election was a partial break in this pattern, since the spread of slavery was the central issue of the election and one could not discuss this issue without discussing the 1857 Dred Scott case, in which the Court held that Congress lacked the authority to prevent the spread of slavery to the territories. Apart from the exceptional 1860 election, however, this pattern basically held until the 1960s.

Deviations from this norm of propriety were risky. For example, in the weeks leading up to the 1932 presidential election, Democratic candidate Franklin D. Roosevelt gave a nationally broadcast speech in which, after noting that Republicans controlled both houses of Congress and the executive branch, he added that Republicans controlled “the United States Supreme Court as well.” Republicans lashed out at Roosevelt, calling his comments “utterly untrue,” “dangerous,” “outrageous,” and a “slur” against the Court. Roosevelt’s advisors worried that his comments would lose him votes, and he said nothing more about the Court for the remainder of his successful campaign.

Four years later, Roosevelt again avoided discussing the Court as a campaign issue. The Court was an issue in the 1936 election, but the ones who discussed it were Roosevelt’s supporters and opponents, not the candidate himself.

In the presidential elections that followed, the Supreme Court barely featured as an issue. This only began to change in the 1950s and 1960s as politicians, including presidential candidates, came to see the Warren Court as a potentially valuable political issue.

The partial breakdown of the propriety constraints on presidential candidates using the Court as a campaign issue had its uncertain—and decidedly ignominious—beginnings in the 1950s. During the 1956 campaign, Republican Vice President Richard Nixon sought to score political points by embracing the Brown v. Board of Education decision. He praised the “great Republican Chief Justice, Earl Warren” for “order[ing] an end to racial segregation in the nation’s public schools.” (Warren had been the Republican governor of California before Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed him to the Supreme Court in 1953.) Democrats condemned Nixon for politicizing the Court. Eisenhower had already gone on record saying he did not believe Court should be a campaign issue. Republicans who were scheming to drop Nixon from the ticket used his comments to support their argument that he was a political liability.

When Nixon ran against John F. Kennedy for the presidency in 1960, the Court was not an issue. Four years later, however, Barry Goldwater, the Republican nominee, broke from tradition for a major party candidate and featured attacks on Warren Court decisions as a major part of his campaign against Democratic incumbent Lyndon B. Johnson.

Rather than engage his Republican opponent on the merits of his critiques of the Court, President Johnson followed precedent and declared that he did not believe the Court an appropriate issue for a presidential election. The opposing side of whatever argument over the Court Goldwater sought to have did not come from his opponent, but from other prominent Democrats.

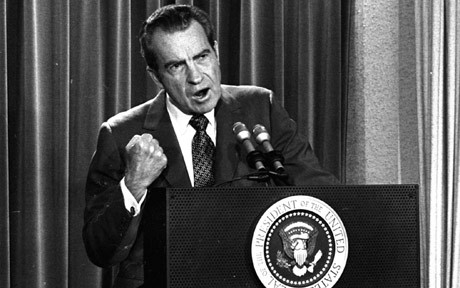

The first time a presidential candidate successfully leveraged the Court as a campaign issue was in 1968. Nixon, the Republican nominee, followed the Goldwater playbook by basically campaigning against the Warren Court, albeit with a much different result on election day. Nixon denounced the “activism” of the Court and promised to appoint judges who would “strictly” interpret the Constitution. He also attacked the Court for being soft on crime and contributing to the nation’s increasing crime rates.

Yet even in 1968, when the longstanding assumption that the Court should not be a prominent campaign issue finally succumbed to the combined pressures of political demands and an unpopular Court, there remained a sense of lurking discomfort with the issue. One of Nixon’s advisers warned Nixon that “any condemnation of the Court will be interpreted as fascist.” Nixon tried to distinguish his support for the Court as an institution from his criticism of particular decisions, and he avoided criticism of the Court’s school desegregation rulings.

The election of 1968 thus weakened but did not sweep aside propriety concerns when it came to using the Court as an issue in presidential campaigns. After Nixon’s demonstration in 1968 of how attacks on the Court could be leveraged into an election victory, the Court became a viable campaign issue for candidates. But it remained a risky one. Candidates still felt the need to tread carefully when engaging the issue, lest they face criticism for politicizing the Court and compromising its independence—criticism not only from opponents, but also from the press and sometimes from members of their own party. Whether the Supreme Court was an appropriate topic on the campaign trail remained a concern for presidential campaigns.

This post was written by ISCOTUS Co-Director and Chicago-Kent Faculty Member Christopher W. Schmidt. It is the fourth of a multi-part ISCOTUS series on the Supreme Court and the 2016 presidential election.