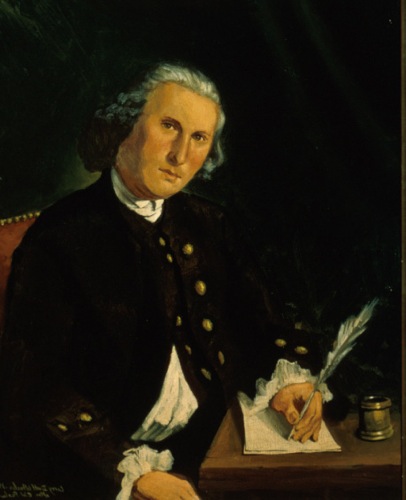

On this day in 1804, the United States Senate created a committee tasked with preparing rules to govern the first impeachment trial of a Supreme Court justice. The previous March, the House of Representatives had voted to impeach Justice Samuel Chase. Chase had been appointed to the Court by George Washington in 1796 and had established a reputation for his staunch, outspoken commitment to the Federalist Party. This gained him the enmity of the Jeffersonian Republicans, who in 1800 had won the presidency and gained control of Congress.

Chase had been particularly vocal in criticizing the Republican repeal of the Judiciary Act of 1801. The repeal abolished a number of newly created federal courts, along with the judgeships Federalists had secured prior to losing power. Chase told a Baltimore grand jury in May 1803 that the repeal would “take away all security for property and personal liberty, and our Republican constitution will sink into a mobocracy.”

At the urging of President Jefferson, Representative John Randolph of Virginia initiated impeachment proceedings against Chase. On March 12, 1804, the House approved eight articles of impeachment against the justice. Among them was the charge that Chase was “continually promoting his political agenda on the bench,” and thereby “tending to prostitute the high judicial character with which he was invested, to the low purpose of an electioneering partisan.”

The House also charged him with “refusing to dismiss biased jurors,” and “excluding or limiting defense witnesses in two politically sensitive cases.” These charges stemmed from two trials over which Chase presided. One was the 1800 treason trial of John Fries, in which Chase had delivered a written opinion that defined treason as a matter of law, without hearing the lawyers’ arguments. Fries’ attorneys withdrew from the case because, claiming that Chase’s conduct had tainted the jury pool, rendering a fair trial impossible. Fries was easily convicted. The other was the 1800 trial of James Callender, who had been indicted under the Sedition Act for publishing a book in which he accused John Adams of being a British sympathizer and a monarchist. The Sedition Act, which a Federalist Congress passed in 1798, made it a crime to bring the president or Congress “into contempt or disrepute.” The House impeachment charge alleged that Chase had acted in a way to ensure Callender’s indictment and that Chase also failed to exclude a biased juror.

The Senate ultimately acquitted Chase of all eight charges on March 1, 1805. None of the articles of impeachment came close to getting the two-thirds majority needed for conviction. His victory is widely believed to be a critical foundation for the principle that the federal judiciary should be insulated—to a large extent—from the partisan machinations of the legislative and executive branches.

Chase went on to serve the rest of his life on the Court. He died in 1811.

This post was drafted by ISCOTUS Fellow Matthew Webber, Chicago-Kent Class of 2019, and edited by ISCOTUS Fellow Bridget Flynn, Chicago-Kent Class of 2019, and ISCOTUS Co-Director Professor Christopher Schmidt.