On October 10, Our Immigration Law Society invited Professor Jack Chin of UC Davis School of Law to share research from his book Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965: Legislating a New America.

On October 10, Our Immigration Law Society invited Professor Jack Chin of UC Davis School of Law to share research from his book Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965: Legislating a New America.

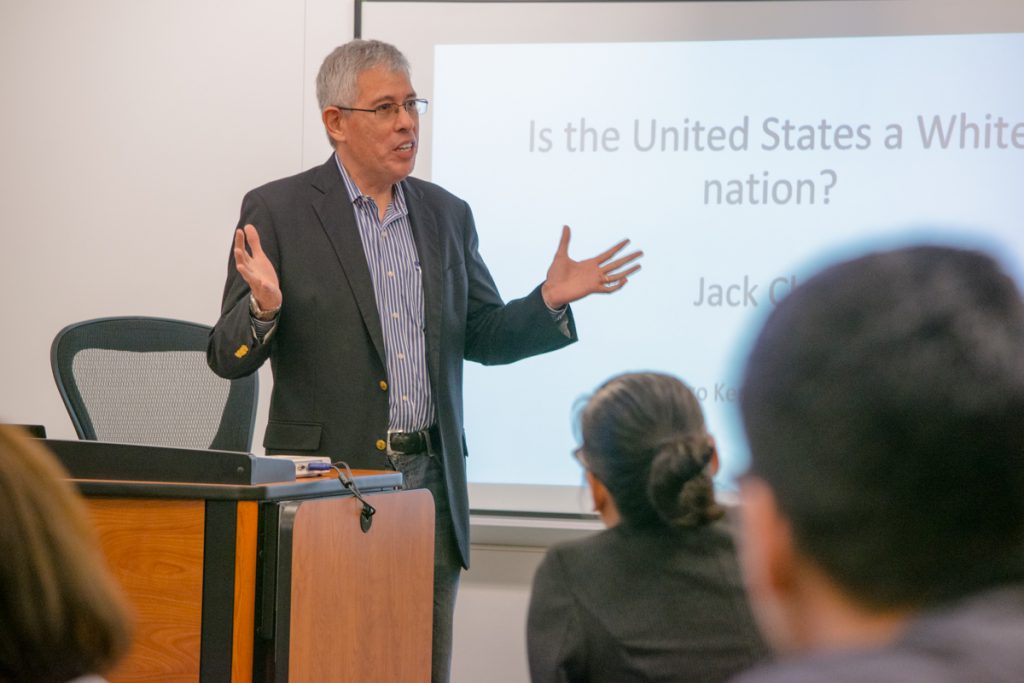

Looking over the history of immigration, he contrasted narratives of white nationalism with civil rights reforms that reduced racial discrimination in American citizenship.

Professor Chin has been actively engaged with immigration and racial discrimination on many levels. His previous scholarship has been cited by the Supreme Court and he’s been working with students to repeal old Jim Crow laws in states that continue to justify discrimination.

He noted the urgency of addressing white nationalism and immigration in our current political context. He described the Trump administration as “one of the most anti-immigrant,” as exemplified by quotes from speeches during the 2016 presidential campaign, family separation policies that aimed to discourage refugees, and other policy changes directed against legal immigrants.

Professor Chin likened these restrictions on immigration to “killing the goose with the golden egg” and spoke of the economic and cultural boon immigrants have been in America — even though our laws have, in the past, limited access to legal immigration based on race.

Race & Immigration: A Legal History

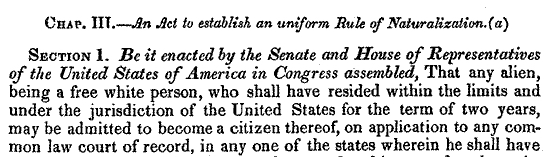

Starting in 1790, the Naturalization Act, signed by George Washington, used the words “free white person” to restrict who was eligible for naturalized citizenship. This law was not repealed until 1952. White nationalists have used this legislation as a touchstone to argue this is foundational to what our nation is meant to be.

Immigration laws that followed continued to depend on the language of the Naturalization Act. In 1849, the Supreme Court defined immigration as a federal issue in the Passenger cases, noting that “We have invited to come to our country from other lands all free white persons, of every grade and of every religious belief.”

In 1857, the Supreme Court decided Dred Scott by using the Naturalization Act again to say “the language of the law above quoted shows that citizenship at that time was perfectly understood to be confined to the white race.”

Legislation & Citizenship

In the late 1800s, some lawmakers were willing to concede rights to nonwhite immigrants more often to solve problems with freed slaves and international relations than from a desire to embrace ideas of racial equality. Professor Chin quoted from the explicitly racial arguments lawmakers used to oppose granting rights to nonwhite state residents or immigrants, even for laws that on their surface seem to not factor race into the rights they grant.

For instance, California Congressman William Higby described Chinese immigrants as “a pagan race,” saying they were “an enigma to me” and “you cannot make good citizens of them” during a debate about the 14th Amendment.

South Carolina Senator John C. Calhoun argued that annexing the people of Mexico would be a “fatal error” if it placed “the colored race on an equality with the white” because “ours is the government of the white man.”

In the immigration debates relating to the Chinese Exclusion Act, Nevada Senator John P. Jones argued that for black citizens “it is no fault of ours that they are here; it is no fault of theirs; it is the fault of a past generation; but their presence here is a great misfortune to us to-day,” and Oregon Senator La Fayette Grover: “when they declared this country to be an asylum for the oppressed of all nations they undoubtedly meant all nations whence they came, people of character and conditions similar to their own” — white.

Until the 1920s, noncitizens could vote in many places if they’d declared an intent to become citizens by going to court, giving their oath and filling out the right documents. Nonwhites couldn’t make that declaration of intent, since they weren’t eligible for naturalization under the 1790 act.

Beyond Immigration Law

Using citizenship as a qualifier helped to continue the promotion of racial discrimination. Referencing the scholarship of Professor Earl Maltz at Rutgers Law School, Professor Chin noted states such as Oregon and Idaho began to use citizenship restrictions to discriminating on issues like owning property or access to employment programs sponsored by the states or the federal government.

Many laws were less focused on immigration and more on allocating property and jobs from the government. The Oregon Donation Land Act of 1850 was a forerunner of every subsequent land giveaway and included explicit racial restrictions, again relying on citizenship or declared intention: “being a citizen of the United States, or having made a declaration according to law of his intention to become a citizen.”

Many laws were less focused on immigration and more on allocating property and jobs from the government. The Oregon Donation Land Act of 1850 was a forerunner of every subsequent land giveaway and included explicit racial restrictions, again relying on citizenship or declared intention: “being a citizen of the United States, or having made a declaration according to law of his intention to become a citizen.”

President Buchanan vetoed the first draft of the law, noting “if this bill becomes a law we may have numerous actual settlers from China and other Eastern nations enjoying its benefits on the great Pacific Slope,” but the legislators who worked on it pointed out that the declaration of intent restriction already excluded those residents..

The Reclamation Act of 1902, which created public works projects like the Hoover Dam and many irrigation projects in the West, also included a restriction in Section 4 that “no Mongolian labor shall be employed thereon” (Mongolian, at the time, was used as a racial category for Asians).

In the Nationality Act of 1940, the Registration of Undocumented noncitizens in 54 Stat 672 applied to those “not racially inadmissible or ineligible for naturalization.” Later laws for the naturalization of veterans were loosened only for Filipinos.

“The Most Effective Civil Rights Act”

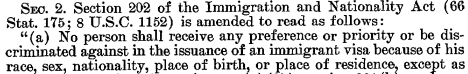

Professor Chin described the Immigration Act of 1965 as “the most effective civil rights act.” Before it was enacted, by design the immigration pool was 80 percent white. Now, with a race-neutral basis, our immigration pool is 75 percent nonwhite.

What changed? There were finally representatives willing to defend changes to our laws on explicitly anti-racist beliefs. The supporters of the Immigration Act of 1965 were the same blocs that voted for the Civil Rights Act and the Voting Rights Act.

Under our current rates of immigration, research institutes have argued that by 2045 to 2050, we will be a majority minority country. But this is not inevitable with the changes to immigration policy under the Trump administration.

Though America began as a country for white citizens, Reconstruction forced our laws to accommodate our black citizens as well. Professor Chin argued that, while Congress made it possible to have a more open definition of who could be American in 1965, this is the moment where the American people will decide if we are really open to people of all races.

The event concluded with a brief question and answer with the audience covering a few specific policies and historical questions.