In the spring of 1892, at the end of the school year, Professor Marshall Davis Ewell wrote a letter of resignation from the Union College of Law in Chicago, where he had been Professor of Common Law for fifteen years. He had earned his law degree from Michigan Law School in 1868 and soon after became a lecturer in Medical Jurisprudence at his alma mater. In 1884, he received his M.D. from the Chicago Medical College. But from 1877 to the spring of 1892, Ewell had enjoyed his time spent teaching at the Union College of Law. The students knew him as “kindly,” and a letter from a former student published in the Chicago Legal News of July 23, 1892 stated that Ewell was “the cleverest instructor of the law college…the students gained more information from Professor Ewell’s lessons and lectures than from the instruction of any other of the able teachers in the college.”

Founded in 1859, the Union College of Law of the Old University of Chicago was the first law school established in Chicago. In 1873, it became partially controlled by Northwestern University, and in 1890, the school lost its charter and became fully absorbed into Northwestern. At that time, the president of Northwestern University, Dr. Henry Wade Rogers, former Dean of the Law Department of the University of Michigan, took control of the law school. During the 1891-1892 school year, Rogers made several changes to the law school. In his resignation letter, Ewell presented a list of four grievances against Rogers. Ewell maintained that Rogers held no faculty meetings, but decided on courses and presented his decisions to each faculty member individually. Furthermore, salaries for law faculty were said to have been reduced by 40% without notice, and at the same time, their hours were doubled. Finally, Ewell alleged a “radical change in the methods of instruction without seeking the views of those who were to carry the changes into effect.” Ewell insisted that enrollment had decreased during Rogers’ first year as president due to dissatisfaction over the decision to drop evening law classes. This “radical change” required all students to be available during the day, which made it impossible for enrolled students to keep their jobs in law offices. Ewell’s speedy exit and subsequent plans to open a new Union Law School caused an ugly ripple in the legal community. Rogers alleged that Ewell was “incapable of keeping up with the rapid pace set for the law department.” Attorney J.S. White, a former student of Ewell’s, pointed out an earlier commendation for Ewell written by Rogers, and asked the readers of the Chicago Legal News, “Is it not somewhat remarkable that the president of Northwestern University did not discover Professor Ewell’s inability to lecture until the question of opening a new law school was brought to light?”

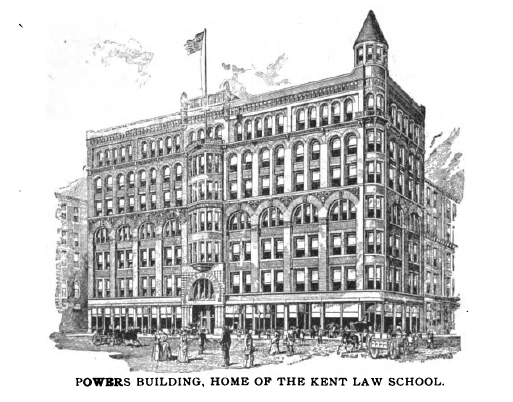

On September 15, 1892, mere months after Ewell’s departure from Northwestern, the new Union Law School of Chicago opened its doors on the fourth floor of the Powers Building, at the northwest corner of Michigan and Monroe. A group of eight professors and lecturers, with Marshall D. Ewell as president and dean, held classes in the evenings from 5:15 to 7:15, with regard to allowing “other necessary work of the student.” As quickly as it opened, the school changed its name from that of its predecessor to the Kent Law School of Chicago. Ewell was a popular professor, and many students were said to have followed him to the new school. The Law Student’s Helper published a highly favorable review of the school’s prime location and course of study in 1894, with sparkling profiles of its few faculty members. The Michigan Law Journal reported enrollment in the first semester as 125, while Northwestern’s enrollment had dwindled to 92. “This unfortunate affair is to be deplored,” an editorial in the Michigan Law Journal remarked, “but, it has resulted in two law schools in Chicago, where there was but one before, it seems that each school will enjoy its share of patronage. As the great and growing metropolis of the west, Chicago is the Mecca of western lawyers, and if New York can support two successful law schools, so can Chicago.”

Kent College of Law ad, from The Chautauquan, Vol. 25, July 1897. IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law Archives.

Chicago, however, had more than one law school before 1892, and would have to support another successful law school before the end of the century. Before the formation of the Kent Law School, several law clerks were meeting in the chambers of Judge Joseph M. Bailey to prepare for the Illinois bar exam. The evening sessions were eventually held as formal classes, and the Chicago Evening College of Law was officially formed in 1888 with Judge Bailey as dean. The following year, the college was reorganized under the name of the Chicago College of Law, and soon after, its title was appended as it became the Law Department of Lake Forest University. As evidenced by its annual growth in graduates, the Chicago College of Law was yet another successful Chicago law school. In September of 1889, 36 students graduated the 2-year course, but by 1895, the number had risen to 168.

By 1900, Ewell’s Kent Law School had moved twice: first, from the Powers Building to a building at the corner of Wabash & Washington, which it shared with the Chicago branch of the Bryant & Stratton Business College, and then again to 59 Clark Street. Meanwhile, the Chicago College of Law had outgrown its quarters in the Appellate Court rooms and moved, in 1890, to the Athenaeum Building at 26 E. Van Buren Street. In May of 1900, the Chicago Tribune reported that the Chicago and Kent Colleges of Law would be consolidated. “The Kent College of Law,” the Tribune stated, would “go out of existence.” It was reported that both schools would hold classes at the Athenaeum Building, and that the new institution would be known as the Chicago College of Law. However, by June of the same year, the Tribune was announcing the upcoming first commencement of the Chicago-Kent College of Law, with a graduating class of 174. Student Pierre G. Beach announced the creation of a “practice court,” and noted the addition of Kent Law School faculty members to the former Chicago College of Law. At the 1900 commencement, President of Lake Forest University James G.K. McClure “declared in his address it was the intention to make the Chicago-Kent College equal to the law departments of any of the great universities of the country.” Clearly, administrators valued each law school, and unified Chicago-Kent with a shared vision for greatness.

In 1904, Ewell, a nationally recognized authority on handwriting, retired from his professorship at the Chicago-Kent College of Law in order to focus on handwriting analysis. He was called upon as an expert in several court cases across the United States until his death in October of 1928.

Resources:

Beach, Pierre G. “Fuller-Law Dept. Lake Forest University.” The Brief, 1900: 109-110.

“Chicago – Kent Graduation.” Chicago Tribune, 3 June 1900: 5.

“Former Dean of Kent College of Law is Dead.” Chicago Daily Tribune, 6 October 1928: 21.

“In Memoriam.” The Bulletin, No. 28. February 1929.

“Kent Law School of Chicago.” The Law Student’s Helper, Vol. 2, No. 1. January 1894: 58-62.

Kirkland, Joseph and Moses, John. History of Chicago, Illinois. Vol. 2, Part 2. 1895.

“Legal Schools to Combine.” Chicago Tribune, 18 May 1900: 9.

“The Resignation of Marshall D. Ewell, M.D.”, Michigan Law Journal, Vol. 1. 1892; 266.

White, J.P. “Hear the Other Side.” Chicago Legal News, Vol. 24, 23 July 1892: 386.