The day was hot, and Henry Walter Beach took a moment to stop his fall plowing and rest his knee, which seized and stiffened in the heat. He removed his soft brown hat and the piece of cotton he kept beneath it, and felt the sharp hand of the sun find the top of his head immediately. Balancing with one knee straight, compensating for the axe wound that had split his kneecap three winters before, he leaned to dip the cotton rag into his water pail. The wet rag offered some relief from the brutal heat which had so far refused to retreat at the advance of the fall season, and with the hat back in place, Henry could almost ignore the oppressive beams of sun overhead. He rallied his tired muscles and made ready to dig back into his plowing when he heard it: a call coming from somewhere near the shack. He stood silently listening for it again, as a much needed breeze excited the dry and crinkled leaves on the thirsty trees. There it was again, for certain this time, a sound traveling across the cracked brown expanse of Michigan farmland from the wood shed. He dropped the plow, tipped the water bucket, and ran to the ramshackle little house. Inside, he dug through his wife Eva’s sewing basket for scissors and thread, and brought these supplies to her in the wood shed, where she labored in the shadowy dark. By evening, two small boys returned from the cow field to find their father rubbing a mewling infant with a gunny sack. “Meet your new brother,” he said, before dunking the stunned baby into a tin wash tub. Of the experience, Rex Ellingwood Beach, born on that day, September 1, 1877, later remarked “I still yell at a cold bath.”

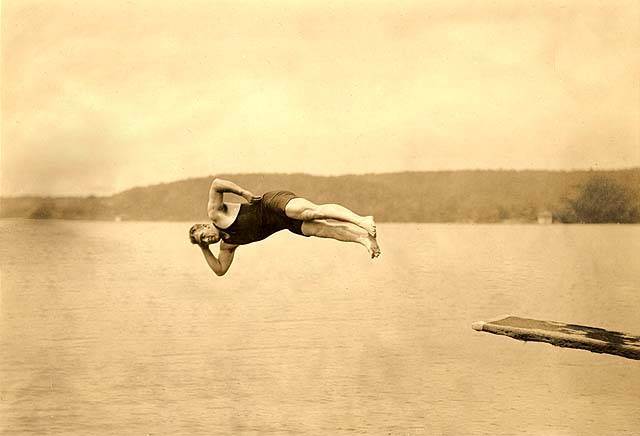

Beach’s childhood was spent on his father’s farm in Atwood, Michigan until the age of seven, when, under the Homestead Act, his family moved to Tampa, Florida. Here, the Beach sons spent their days diving, swimming, and running barefoot on beaches. Their father soon opened a broom shop in the hopes of raising money to send his three sons to school, which he did, and eventually the wild young Rex Beach was corralled and forced to put on shoes. Rex was sent to Rollins College in Winter Park, Florida. Though the dormitories had no running water and the school had little financial support with which to better itself, Beach found happiness swimming in clear spring water, diving from rocks, and spending hot afternoons “refresh[ing] the girls by allowing them to watch us cavort in the cool, clear depths.” He spent his monthly allowance on soda pop. “I indulged myself to the full and lurched back to the campus belching luxuriously in assorted flavors,” he wrote. At Rollins, Beach also had several disagreements with the college administration. In 1892, he was severely reprimanded by the college president for the “heinous” crime of sailing on a Sunday. The next week, he was suspended for attending a late night party in Orlando.

Rex Beach diving, date unknown. Department of College Archives and Special Collections, Olin Library, Rollins College.

Though he was eventually reinstated at Rollins, Beach was certain that his calling was to become a lawyer, and left the school a year early bound for Chicago, where his two older brothers practiced law. “I proposed to enter their office, rapidly make myself a partner in the firm, then become a Justice of the Supreme Court and live in Washington,” he wrote of his plans. “There being nine Justices and only one President it looked like a cinch. Furthermore I had always wanted to own a black lounging robe.” As he waited for classes at the Chicago College of Law at Lake Forest University to start, he made himself useful around the office, and “began to shadow box with my chosen profession.” Upon hearing that the Chicago Athletic Association fed its team members meat on a regular basis, Beach introduced himself to the captain of the football team, Mr. William Hale Thompson, future mayor of Chicago. Beach boasted of his football experience, when in actuality he had none. As he talked, Thompson dined on “a burial mound of spaghetti au gratin,” which made Beach’s mouth water and his tale taller. Somehow, he managed to get a spot on the C.A.A. football team, where he “missed not a single meal at the training table.” Through football season and into water polo season, Beach attended law school in Lake Forest and played on C.A.A. teams, alternating his time between reading law books and studying sports rules. That summer, however, the discovery of gold in the Klondike sent the country into a fervor and Beach decided that since it would quite possibly take a while to get into the Supreme Court, and since athletic injuries would soon render him useless, he may as well take some time off and try his hand at gold mining. For two years, he traveled the Yukon with nothing but a rifle, a fur-lined sleeping bag, and a mandolin, and returned with only the mandolin, sans strings. He re-enrolled in law school in 1899, this time the Kent College of Law, which was only months away from fully merging with the Chicago College of Law to become today’s Chicago-Kent.

Rex Beach, c. 1894. Department of College Archives and Special Collections, Olin Library, Rollins College.

Though he had begun his study of the law with no doubt that it was to be his profession, Beach felt differently about his calling through his second year of law school. “It was the salmon in me, no doubt; an upstream urge driving me back to the spawning grounds. Anyhow I no longer had the urge to wear a Supreme Court parka.” The years spent hiking from town to town, sleeping on fishing boats, and searching in vain for payloads of gold had inspired him to seek out more adventures. He spent the summer of 1900 in Alaska, where he struck a small amount of gold near Nome. Two years later, he found not only a mining claim for sale, but a purchaser for it, whom he talked into making him a partner, “using much the same technique I had employed on Big Bill Thompson.” He wandered Alaska, hiking through scalded valleys where the earth exhaled volcanic gases, and traversing frozen mountain passes cut by glaciers. He visited mountain towns, got into

“scraps” in variety theaters and at card games, and bet on boxing matches between road crew members and businessmen. He met Edith Greta Crater, then a young proprietor of a small mining hotel, whom he later wrote was “as independent, as self-confident, and as businesslike as a man.” As “an old man of twenty-four,” and a married man at that, he returned to Chicago and sold life insurance for a short time, and later building materials. A successful salesman, he soon had the means to join the C.A.A. as a full member, and captained the water polo team. In 1904, his company was hired to install boilers at the St. Louis World’s Fair (The Louisiana Purchase Exhibition). The 1904 Summer Olympics were being held concurrently in the city, as a part of the Exhibition, which gave Beach the chance to compete. In St. Louis, Beach competed as an individual and won the one-mile handicap swimming race. He then competed as a member of the C.A.A.’s water polo team, which placed second. However, handicap races are not counted as Olympic events, and due to a disagreement over the disqualification of a German team, the International Olympic Committee considered the water polo match an exhibition game, not an Olympic event, so Beach returned to Chicago without his gold and silver medals.

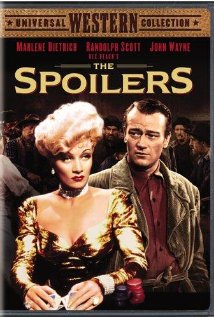

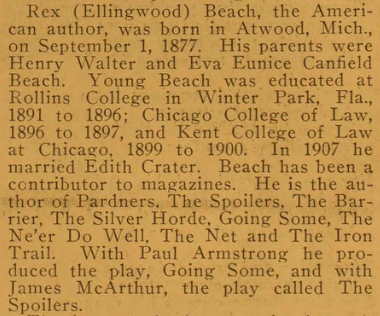

On a sales trip, Beach was pleased to run into an acquaintance from Alaska, and was inspired by the reminiscences they shared with one another. Yet another new interest began to bloom for Beach: fiction writing. He wrote as he traveled, in rail cars, in waiting rooms, and anywhere he could fit his suitcase onto his knees to use as a writing desk. His stories of Alaskan travels began to appear in magazines around the country, beginning with “The Mule Boy and the Garrulous Mute,” published in McClure’s Magazine in 1903. With encouragement from the editors of both McClure’s Magazine and Everybody’s, Beach began to work on his first novel, The Spoilers. In 1906, the book became a bestseller at 700,000 copies, and was later made into a movie five times, most famously in 1942, starring Marlene Dietrich and John Wayne. It earned Beach the reputation of “The Victor Hugo of the North.” Beach entered negotiations with the motion-picture industry carefully, calling it “eccentric, mildly mad…It runs a fever that infects most of the people in it.” He was one of the first writers to stress the importance of the inclusion of the author’s name in film adaptations, and insisted that he be credited on all film versions of his novels. Over the next 40 years, he wrote adventure stories set in fictional Alaskan towns and in the wild surrounding lands, recounting what he had witnessed, and embellishing here and there with that same talent that had earned him that spot on Thompson’s football team and a financial partner in gold mining. His novels The Barrier and The Silver Horde made the bestseller lists in 1908 and 1909, respectively, while the allure of the Alaskan wilderness and Gold Rush Fever still captivated the public. Of his 33 novels, 14 were made into movies, and on each he received the screen credit he demanded.

Excerpt from The Chicago-Kent Bulletin, Volume 1, Issue 5, 1916. AC025, IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law Archives.

Though he never became a lawyer, Beach continued writing for the rest of his life. At the time of his death in 1949, he had written countless short stories and numerous books, and his screenplays spanned the era of silent movies into the days of full-color motion pictures. He received an honorary degree from Rollins College in 1927, and both he and Edith Greta were later buried on campus near the Alumni House. Beach made the most of every experience, every hardship, and every memorable moment in his life by translating them into captivating adventure stories, because, as he put it, “Life isn’t easy or painless. That’s what makes it a swell adventure.”

Resources:

Beach, Rex Ellingwood. Personal Exposures. 1940.

Gayle Prince Rajtar, Steve Rajtar. Winter Park Chronicles. 2011.

“Rex Beach – From Forelock to Brisket”. From the Rollins Archives. 2012.

“Rex Ellingwood Beach (1877-1949): Famous Rollins Alumni and Prolific Outdoor Novelist”. Rollins Archives.