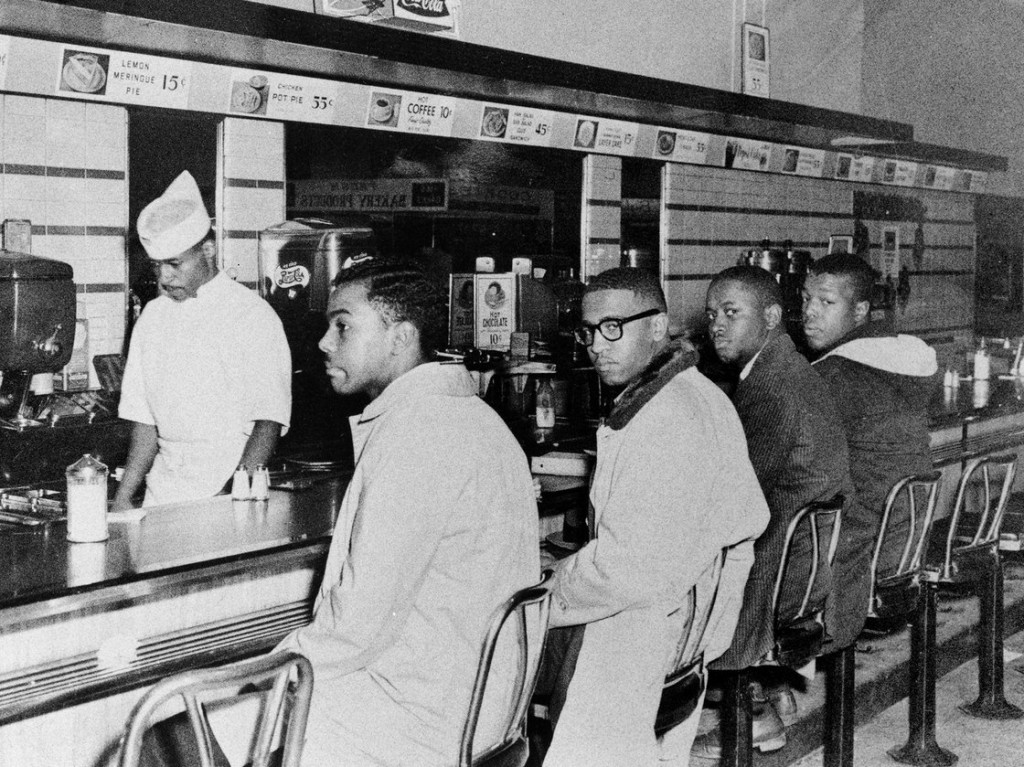

The “Greensboro Four”: from left, Joseph McNeil, Franklin McCain, Billy Smith and Clarence Henderson. (Jack Moebes/Greensboro News & Record)

Franklin McCain died last Thursday, January 9. He was one of the “Greensboro Four,” the four freshman at an all-black college in Greensboro, North Carolina, who, on February 1, 1960, requested service at the “whites-only” lunch counter of their local Woolworth’s and, when refused, remained seated on their stools. With that simple act of defiance, McCain and his three classmates set in motion events that would transform the civil rights movement.

On the occasion of McCain’s passing, it is worth looking back at why that February afternoon in 1960 proved such a momentous turning point in our nation’s history.

No one at the time could have envisioned the dramatic consequences of this quiet protest. The Greensboro Four were not motivated by any grand visions of inspiring a social movement. Their perspective was narrower, more personal.

It all began with a conversation—four young men, sitting in a dormitory room, discussing their hopes and their frustrations. Of the many topics they talked about in these “bull sessions,” the one they kept returning to was the challenge of leading a dignified life in the Jim Crow South. They talked, and they talked some more. And then, as one of them put it, “we just got tired of talking about it and decided to do something.”

They walked downtown and sat down at the Woolworth’s lunch counter. “I’m sorry, we don’t serve colored in here,” the waitress told them. Like most department stores in the American South, the Greensboro Woolworth’s welcomed African American customers into all parts of the store, but with one restriction: blacks were not allowed to sit down at the lunch counter. They sat until closing and then returned to their dorms.

They returned the following morning, this time with reinforcements, twenty-one in total. The students sat in shifts throughout the day. They talked quietly among themselves; some brought books and used the time to keep up with their school work. The next morning they were back again. By the end of the week two hundred students had taken part in the protests.

Then the sit-ins spread beyond Greensboro. Within a month of the first protest, students had organized sit-in demonstrations in 30 cities in 7 states. A month later, it was 48 cities in 11 states. An estimated 50,000 protesters eventually took part in the sit-in movement. Hundreds were arrested, charged with trespassing on private property or disorderly conduct.

The Greensboro protests were not the first time African Americans protested restaurant discrimination by refusing to leave when being denied service. What separated these sit-ins from all that came before was what followed. These protests inspired others to march, picket, boycott, sit-in, even to go to jail—things they would never have imagined doing before being moved by the images of young men and women quietly sitting on stools at a lunch counter. A week of remarkable events in Greensboro turned into an inspired assault on racial practices throughout the South. The sit-ins became a movement.

[More on Oyez: check out this list of sit-in cases that made it to the US Supreme Court]

Why did this particular protest, this bold but quite small-scale request for a simple cup of coffee, catalyze all this? In this case, the cliché fits: The Four were in the right place at the right time. The larger civil rights movement was at a crossroads in the winter of 1960. Efforts to rally the movement around voting rights had failed to take off. The campaign for desegregated schools was bogged down in litigation trench warfare, as southern states used the courts to slow to a trickle the process of implementing Brown v. Board of Education. Young African Americans like McCain saw existing civil rights organizations as controlled by an older generation that was too committed to litigation and lobbying. They were impatient and they were eager to act for themselves.

The students also benefited from uncertainty over the legality of the particular discrimination they were protesting. By 1960, whether the Brown’s non-discrimination principle reached (or would soon reach) privately owned public accommodations was an open question. The students and their supporters often defended their demands as grounded in constitutional principles. This was a claim the Supreme Court never endorsed but Congress effectively would when it prohibited discrimination in public accommodations throughout the nation in the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

The sit-in movement, which Franklin McCain played a central role in creating, launched a new chapter of the struggle for racial equality, one that was more openly defiant, more participatory, and, in many ways, more successful, than anything that had come before.

By

By

Leave a Reply