The Supreme Court heard oral argument in the historic case of Obergefell v. Hodges, the same-sex marriage cases, which ask two questions: 1) Does the Fourteenth Amendment require a state to license a marriage between two people of the same sex?, and 2) Does the Fourteenth Amendment require a state to recognize a marriage between two people of the same sex when their marriage was lawfully licensed and performed out-of-state?

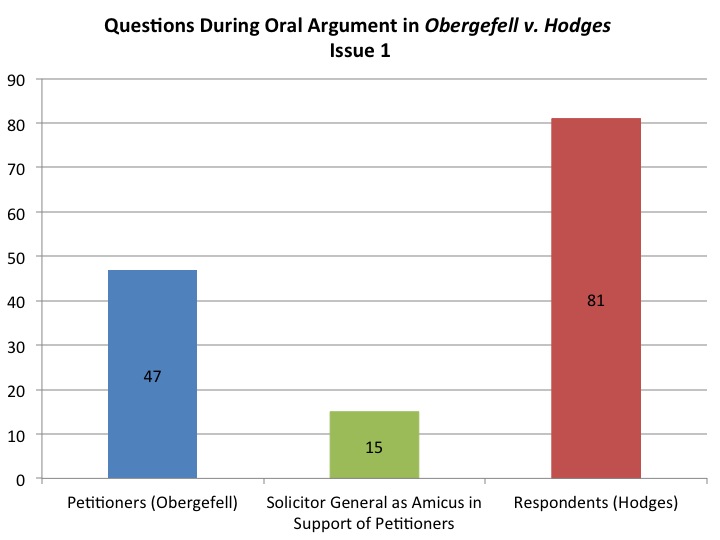

Figure 1

On the first question, the total question count favors the Petitioners (Obergefell), as shown in Figure 1. The Court asked the Respondents 19 more questions than it asked the Petitioners’ side (including the Solicitor General as amicus).

The question count by Justice , however, provides the real story. As expected, the Justices appear to be divided along ideological lines. The 4 liberal Justices asked far more questions to the Respondents, suggesting a leaning to the Petitioners: Ginsburg (+5), Breyer (+15), Sotomayor (+8), and Kagan (+27). Justice Kagan asked an unusually high number of questions (28) to the Respondents, but only 1 to the Petitioners’ side. Her 27-question differential is essentially responsible for the difference in the total question count above.

By contrast, 3 conservative Justices asked far more questions to the Petitioners, which suggests a leaning to the Respondents: Roberts (+8), Scalia (+12), and Alito (+19). Justice Thomas asked no questions, but one can predict he would join this conservative bloc.

So how will Justice Kennedy, the swing vote, decide the first issue? He asked 2 more questions to the Respondents (8 questions total compared to 6 questions for the Petitioners’ side, including the Solicitor General as amicus in support of the Petitioners). It’s a slim margin, but it’s noteworthy that Justice Kennedy asked the Petitioners and the SG only 3 questions each, but the Respondents 8 questions. This is what I call an “asymmetrical case” with 2 lawyers on one side and 1 lawyer on the other side. One might expect the presence of the second lawyer on one side might inflate the question count somewhat, given that the Justices might want to ask similar questions to both attorneys on one side–thereby inflating that side’s question count. In this case, however, the total number of questions asked by Justice Kennedy to the Petitioners and SG is still lower than the number he asked the Respondents.

Based on these numbers, I predict a 5-4 victory for the Petitioners on the first issue, with Justice Kennedy in the majority. The Petitioners argued that the Fourteenth Amendment requires a state to license a marriage between two people of the same sex.

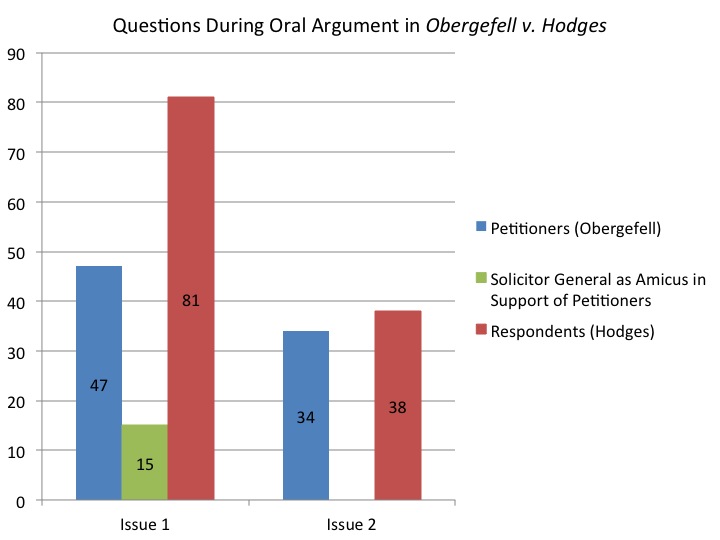

Figure 2.

On the second question, the total question count slightly favors the Petitioners. The Court asked the Respondents 4 more questions than it asked the Petitioners, as shown in Figure 2 above. But, again, the real story is the question count by Justice, which shows the same ideological breakdown among Justices as in the first issue, though with much smaller margins (the Justices didn’t ask many questions related to the second issue). The 4 liberal Justices asked the Respondents more questions: Ginsburg (+1), Breyer (+4), Sotomayor (+7), and Kagan (+2). Meanwhile, 3 conservative Justices asked the Petitioners more questions: Roberts (+1), Scalia (+1), and Alito (+7).

Justice Kennedy asked only 1 question, and it was to the Petitioners. Does that suggest Justice Kennedy is leaning to the Respondents? Possibly, but it’s an even slimmer reed to base a prediction than the 2-question margin in the first issue. Of course, if the Court ruled in favor of the Petitioners on the first issue, it would not even be necessary to decide the second issue.

Given the volume of questions on the first issue, I see the Court deciding the case on the first issue. The question count by Justice is close. But it favors slightly the Petitioners. I’ll go with a victory for the Petitioners on the first issue or, alternatively, on the second issue.

Your analysis assumes that the side that is asked more questions will lose. Do you have any empirical support for this assumption? Has it been true on a regular basis in SCOTUS decisions?

Yes, this method has been validated as statistically significant by prior empirical studies. I’ve cited a few here: http://blogs.kentlaw.iit.edu/iscotus/lee-predicting-winners/