On this day in 1991, the Senate confirmed Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court. Thomas, who President George H.W. Bush nominated for the seat that opened after the retirement of Thurgood Marshall, the first African American Supreme Court Justice, experienced one of the most contentious confirmation processes in American history. Critics of Thomas’ conservative record as a Reagan administration official and then a federal appeals court judge opposed his appointment from the start, particularly in light of the liberal legal icon whose seat he was to occupy. The nomination then took a scandalous turn when Anita Hill, a law professor at the University of Oklahoma, accused Thomas of sexually harassing her when he was her supervisor at the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Thomas’s nomination barely survived the ensuing controversy. The Senate vote to confirm him was 52-48.

Clarence Thomas was born into poverty in rural Georgia in 1948. Thomas’ grandfather came to play a particularly influential role in his life, as he would detail in his memoir, My Grandfather’s Son. Thomas initially planned to become a priest, but after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., Thomas became disillusioned with the Catholic Church for not taking a strong enough stance on civil rights issues. He went to Holy Cross College, where he earned a degree in English Literature. He then attended Yale Law School, the beneficiary of an affirmative action program designed to bring more African American students to the school.

Before his nomination to the Supreme Court, Thomas spent the majority of his career in government. After passing the bar in 1974, he worked for the Attorney General of Missouri until 1977, when he became a legislative assistant to Senator John C. Danforth. Four years later, President Reagan appointed him Assistant Secretary for Civil Rights of the Department of Education, and the following year he was appointed Chairman of the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. After serving eight years at the EEOC, President Bush appointed Thomas to the D.C. Circuit Court of Appeals, where he served for only 19 months before being nominated to the Supreme Court.

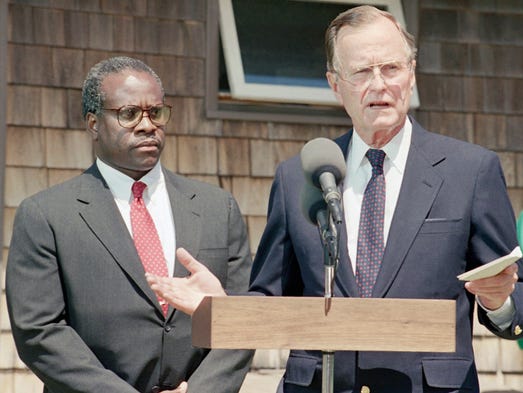

President Bush insisted that Thomas was not intended to fill a “quota” by having a black justice on the Court. “I expressed my respect for the ground that Mr. Justice Marshall plowed,” the President explained, “but I don’t feel there should be a black seat on the Court or an ethnic seat on the Court.” Bush insisted that he simply picked the most qualified person for the position.

Anita Hill’s shocking testimony before the Senate Judiciary Committee, just days before the confirmation vote, sparked a media explosion and threw Thomas’ confirmation in doubt. Thomas lashed out, accusing his opponents of engaging in a “high-tech lynching.” After being confirmed by the narrowest margin for approval of a Supreme Court justice in more than a century, President Bush, declared, “Judge Thomas has demonstrated to the Congress and to the nation that he is a man of honesty, dedication, and commitment to the Constitution and the rule of law.”

This post was drafted by ISCOTUS Fellow Michael Halpin, Chicago-Kent Class of 2020, edited by ISCOTUS Fellow Elisabeth Hieber, Chicago-Kent Class of 2019, and overseen by ISCOTUS Co-Director Professor Christopher Schmidt.