Why in the world did Wendy Vitter refuse to declare her allegiance to that constitutional holy of holies, Brown v. Board of Education?

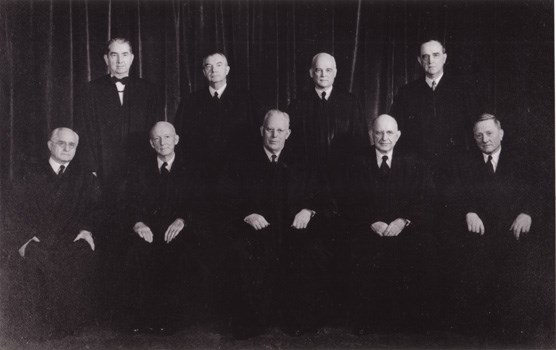

Harris and Ewing/Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division

During Vitter’s confirmation hearings this week, Senator Richard Blumenthal asked the federal district court nominee whether she believed Brown was rightly decided. “Senator, I don’t mean to be coy,” she responded,

but I think I get into a, uh, difficult area when I start commenting on Supreme Court decisions which are correctly decided and which I may disagree with. Again, my personal, political, or religious views I would set aside. That is Supreme Court precedent. It is binding. If I were honored to be confirmed I would be bound by it and of course I would uphold it.

Blumenthal repeated his question. Again Vitter performed her duck and weave. “I would respectfully not comment on what could be my boss’s ruling, the Supreme Court. I would be bound by it and if I start commenting on I agree with this case or don’t agree with this case, I think we get into a slippery slope.”

A video clip of Vitter’s awkward exchange on Brown soon bounced around social media. Predictably, the nominee earned mostly scathing reviews for her performance.

This isn’t the first time we’ve seen this puzzling dance around what most people consider the most uncontestable of Supreme Court precedents. At his confirmation hearing a little over a year ago, when posed this very same question by this very same questioner, Neil Gorsuch also avoided a direct answer. Senator Blumenthal asked Gosuch whether he agreed with the result in Brown. Gorsuch responded, “Brown v. Board of Education corrected an erroneous decision—a badly erroneous decision—and vindicated a dissent by the first Justice Harlan in Plessy v. Ferguson where he correctly identified that separate to advantage one race can never be equal.” Blumenthal reiterated his question: did Gorsuch agree with the result in Brown? “Senator, it is a correct application of the law of precedent,” Gorsuch responded. The senator noted that when John Roberts faced this same question in his confirmation hearing, he said simply “I do.” “Would you agree with Judge Roberts?” Blumenthal pressed. Gorsuch still resisted the obvious one-word three-letter response. He instead offered a tentative, roundabout, but seemingly affirmative answer response: “Senator, there’s no—there’s—there’s no daylight, here.”

Since Vitter’s artless performance was basically a replay of the strategy Gorsuch deployed more skillfully at his confirmation hearing, we can assume that the Brown bob-and-weave is the current strategy for Republican-nominated judicial nominees.

What’s going on here? Why don’t these nominees take the less controversial and less awkward path and just straight up say: “Brown was correctly decided. Of course I agree with Brown. Next question?”

Commentators have offered three different explanations. One I don’t believe is plausible; the other two make more sense. But none seem strong enough to justify the tactic.

The explanation I find implausible is that the reason these nominees have so much trouble simply expressing their support for Brown is that they are opposed to or ambivalent toward racial desegregation. This is the line Democrats and liberal groups have pressed to mobilize opposition to Vitter’s nomination.

The reason this strikes me as an implausible explanation is that even if, for the sake of argument, we assume a nominee truly held such beliefs, and if that nominee wanted to convey this point, the nominee could simply say so. This would never happen, of course, because expressing such an openly racist position would be automatically disqualifying. This being the case, why, as a strategic matter, would a nominee who hypothetically held such retrograde attitudes want to shine a light on this fact by botching the Brown question? If skeptical senators were truly worried that the nominee was an avowed segregationist, they could just ask the nominee straight up: do you support racial segregation? She would, of course, deny the charge (as Vitter did later in her testimony, when given the opportunity by a supportive Republican senator). It’s hard to think of why it would make any strategic sense for a racist nominee—who would of necessity have to lie when faced with the “are you a segregationist?” question—to not just lie when faced with the “do you accept Brown?” question. In this sense, Brown doesn’t work as a dog whistle; it’s just a regular whistle, loud and clear.

A more plausible explanation is that difficulty with directly embracing Brown stems from concerns some conservative jurists have with the reasoning the Court used to arrive at its landmark ruling. Originalists, in particular, are often put on the defensive when asked to explain how their preferred approach to constitutional interpretation squares with Brown. In Brown, Chief Justice Earl Warren quite explicitly rejected the history of the framing and ratification of the Fourteenth Amendment as a basis for his ruling, relying instead on twentieth-century understandings about the role of public schools in American society and the harms of racial segregation. Justice Scalia got so exasperated with this line of challenge to his jurisprudence that he called it “waving the bloody shirt of Brown.” Maybe these nominees’ unwillingness to just say Brown was correctly decided indicates lingering doubts with the way in which the Brown Court arrived at its holding.

While this explanation identifies a perceived vulnerability for some conservative jurists, it too is insufficient to fully explain the chosen tactic. After all, Justice Gorsuch, in his exchange with Senator Blumenthal, eventually came around to basically saying that Brown was justified on originalist grounds. This is a position Justice Scalia also came to embrace, and various originalist scholars have gone to great lengths to try to support this point. So even if these nominees wanted to take issue with how Warren went about arriving at his decision, they could simply say that Brown was correct, but that they would have taken a different path to reach the holding.

This then brings us to the explanation the nominees themselves offer for the Brown duck and weave: they want to avoid saying anything of substance on any Court ruling, and they are unwilling to make an exception for Brown.

Here was what Gorsuch said at his confirmation hearing: “If I were to start telling you which are my favorite precedents or which are my least favorite precedents or if I view a precedent in that fashion, I would be tipping my hand and suggesting to litigants that I’ve already made up my mind about their cases. That’s not a fair judge.” Gorsuch went on to explain that he wanted to avoid “giving hints or previews or intimations about how I might rule.” This was also the explanation that Vitter was struggling toward in her response to Blumenthal. And it is the explanation that Vitter’s defenders have offered.

But I still have difficulty seeing why a nominee who has a general policy of avoiding discussion of precedents would not make exceptions for certain well-settled cases.

Let’s apply Gorsuch’s explanation to Brown. The reasoning here would seem to be that if a nominee unequivocally accepted Brown as correctly decided, then a potential litigant who walks into the Supreme Court hoping to get the justices to overturn Brown would somehow be disadvantaged because one or more of the justices had already expressed the opinion that the decision was correct. And this would not be fair.

Can this be right? Of course a lawyer who walks into the Court expecting the justices to overturn the most revered decision of constitutional law is going to know that she is walking into a judicial buzz saw. Who are we fooling here? Put another way, do we really want a judicial system in which no precedent can be regarded as solid? Do we really want a lawyer who dreams of interring Brown alongside Plessy and Lochner in the dustbin of constitutional history to feel she has a fair shot, that she’s going to be speaking to a bench that is completely open-minded on this question?

This question is at the heart of an important forthcoming article in the Chicago-Kent Law Review by Lori Ringhand and Paul Collins. Here’s what they conclude:

[C]onfirmation hearings function as a high-profile public forum in which we as a nation affirm our shared constitutional commitments. If future nominees follow Gorsuch in refusing to provide firm opinions on even our most iconic cases, we lose an important tool in ensuring that the individuals selected to serve on the Supreme Court accept the constitutional settlements reached by each generation of Americans.

Ringhand and Collins raise a key issue here, one that often gets lost beneath the posturing and politics that characterize judicial confirmation hearings: What can we expect to achieve from these hearings? It may be too much to ask for a rigorous debate over constitutional principles. It may be too much to ask for deep insights into a nominee’s thinking on the most pressing of constitutional controversies. But is it too much to ask that we use confirmation hearings as opportunities to recognize that in our moment of ideological fracturing, there remains—or at least should remain— a constitutional common ground on which we all stand?

This post was written by ISCOTUS Co-Director and Chicago-Kent Faculty Member Christopher W. Schmidt.