The Supreme Court heard oral argument in two cases on Monday, the first cases for 2015. I’m predicting the winners of the Supreme Court cases based on the number of questions asked during oral argument. For more about this method, see my post on last Term’s Aereo case. For all of my predictions this Term, click here.

Reed v. Town of Gilbert, AZ asks whether the Town of Gilbert’s mere assertion that its sign code lacks a discriminatory motive renders its facially content-based sign code content-neutral and justifies the code’s differential treatment of petitioners’ religious signs.

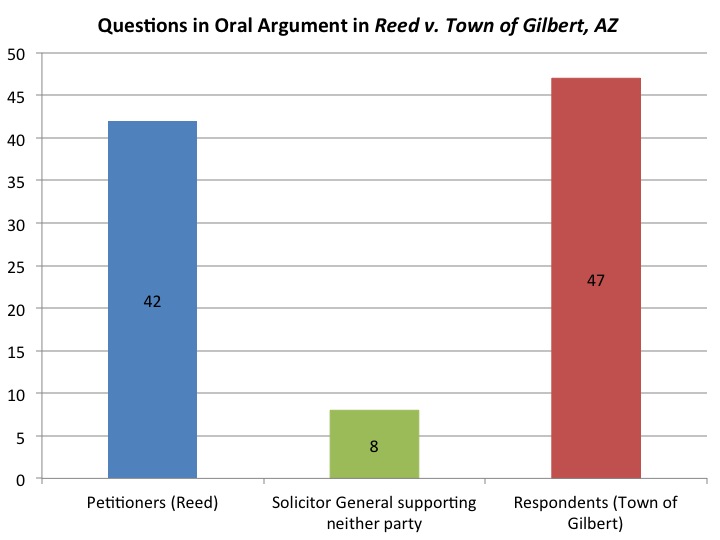

This case was somewhat difficult to call, but I predict a victory for the Petitioners (Reed) in their First Amendment challenge to the Town of Gilbert’s differential treatment of religious signs (compared to political or ideological signs). As indicated in Figure 1, the Justices asked the Petitioners 5 fewer questions than the Respondents. The difference in the numbers of questions is not large, but suggests a win for the Petitioners.

Figure 1.

Moreover, looking at the question counts by Justice shows 3 Justices who had large disparities in questions, asking far more questions to the Respondents: Justices Scalia (+11), Ginsburg (+8), and Kagan (+6). By contrast, only 2 Justices asked far more questions to the Petitioners: Chief Justice Roberts (+5) and Justices Kennedy (+9). Justices Breyer, Alito, and Sotomayor did ask 2 more questions to the Petitioners—which cuts somewhat against my prediction—but the difference in questions is so small that I would place less stock in it.

It is also possible that the Court could agree with the Solicitor General’s position and reach the same result as sought by the Petitioners. The Petitioners argued the proper test was a form of strict scrutiny in which the motives of the enactors of the sign code does not matter. The Solicitor General sided with neither party, but argued that the Town’s sign code violated the First Amendment under intermediate scrutiny.

The second case, Oneok, Inc. v. Learjet, Inc., asks whether the Natural Gas Act, which occupies the field as to matters within its scope, preempts state-law claims challenging industry practices that directly affect the wholesale natural gas market when those claims are asserted by litigants who purchased gas in retail transactions.

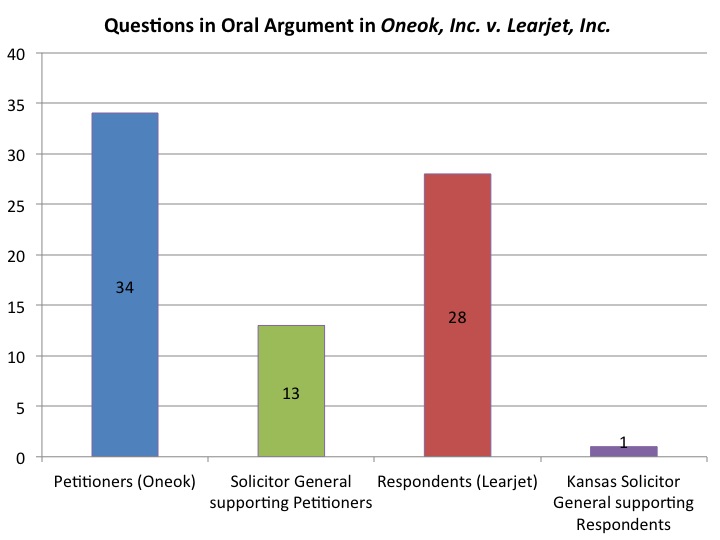

This case was easier to predict. Each side had 2 advocates (i.e., an amicus curiae on its side). I predict a victory for the Respondents (Learjet, Inc.), which argued for affirming the Ninth Circuit’s decision holding that the state law claims were not preempted. As indicated in Figure 2, the Court asked the Petitioners 6 more questions. Moreover, when the questions to the amicus curiae for each party is included, the Court asked 18 more questions to the Petitioners’ side (47 to 29 questions).

Figure 2.

The question count by Justice makes me a little less confident in my prediction, however. Some of the Justices (Thomas and Alito) didn’t ask any questions. Two Justices asked far more questions to the Petitioners’ side: Justices Ginsburg (+6) and Kagan (+15). One Justice asked far more questions to the Respondents’ side: Justice Scalia (+4). Three Justices asked only 1 more question to a side: Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Sotomayor (both +1 to the Respondents’ side) and Justice Kennedy (+1 to the Petitioners’ side). Justice Breyer asked 2 more questions to the Petitioners’ side. These numbers paint a closer call than the overall question count would predict, but the question counts by individual Justice still favor the Respondents.