By Colleen Canniff

“Hopefully the Class of 2018 is paying attention, because otherwise the UEA is going to have to rape harder…”

In the fall of 2014, the incoming University of Chicago freshman class and the wider University of Chicago (UC) community were targeted and threatened as an anonymous hacker group, UChicago Electronic Army (UEA), posted the name of a sexual assault survivor and activist, purportedly in retaliation of the posting of The Hyde Park list. The Hyde Park List, posted to Tumblr, was compiled by and for UC students and contained a list of UC students who, according to the list, are “individuals we would warn our friends about, because of their troubling behavior towards romantic or sexual partners.” The original purpose of the list was to “[keep] the community safe—since the University won’t.” One could argue that the UEA’s actions were out of a concern of denying due process to the students named. But their method—threatening rape, and naming and identifying a victim of sexual assault—is a prime example of a troubling trend on the internet: using threats of sexual violence to silence individuals with whom a group of people doesn’t agree with. As threats go online, the law is racing to keep up.

The UC incident is just the tip of the digital-assault iceberg. Other reports of online sexual assault such as the iCloud hack, theft, and online release of dozens of celebrities’ personal nude photos, YouTuber Sam Peppers’ videos of sexually harassing women on the street, and the continued threats against Anita Sarkeesian, founder of Feminist Frequency (a website where she discusses and critiques female representations in videogames), exemplify the pervasiveness of online sexual violence against women.

The hack and subsequent release of celebrities’ personal photos incited a Twitter discussion and the act was termed a “digital rape” and “digital assault.” Others, such as Lena Dunham, shared in these sentiments with tweets which included, “The way in which you share your body must be a CHOICE” and “Seriously, do not forget that the person who stole these pictures and leaked them is not a hacker: they’re a sex offender.” The hack was an invasion of the reasonable expectations of privacy and the dissemination of these images lacked the explicit consent of the women in the photos.

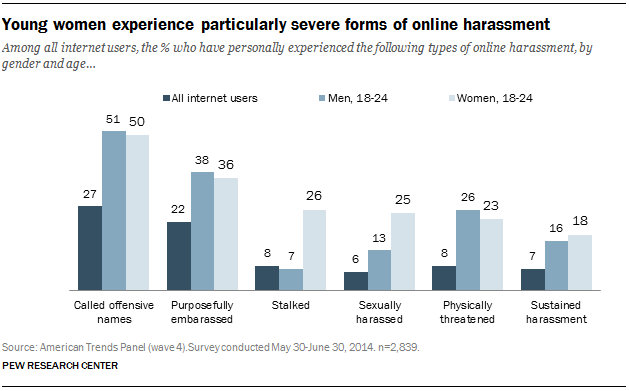

It is important to remember that these instances of “digital assault” are nothing new. In an October 2014 Pew study, 18% of all internet users reported experiencing a “more severe” type of online harassment such as physical threats, sustained harassment, stalking and sexual harassment. The same study reported that women between the ages of 18 to 24 experienced the highest levels of being stalked online (26%) and being sexually harassed online (25%). Nearly one in five internet users have reported witnessing someone being sexually harassed online. Even employees of the U.S. National Security Agency have been accused of intercepting and circulating nude images of the individuals they surveil.

It is important to remember that these instances of “digital assault” are nothing new. In an October 2014 Pew study, 18% of all internet users reported experiencing a “more severe” type of online harassment such as physical threats, sustained harassment, stalking and sexual harassment. The same study reported that women between the ages of 18 to 24 experienced the highest levels of being stalked online (26%) and being sexually harassed online (25%). Nearly one in five internet users have reported witnessing someone being sexually harassed online. Even employees of the U.S. National Security Agency have been accused of intercepting and circulating nude images of the individuals they surveil.

There are many issues that complicate the remedy of sexual violence in everyday life. These issues multiply online. Threats and acts of sexual violence online often include privacy violations as well as real and present danger to those who are targeted. Anita Sarkeesian was threatened with graphically violent messages that included her and her parents’ home addresses, driving her from her home to and inciting her to cancel speaking engagements.

The perpetrators of online threats and acts are often anonymous. In a recent survey of those who had experienced online harassment, 38% said the perpetrator was a stranger and another 26% did not know the real identity of the perpetrator or perpetrators.

Threats of violence, when connected to a person’s Facebook, Twitter, LinkedIn, YouTube, or other myriad accounts, become a part of that person’s digital footprint. For example, if the rumor that a college student earned her 4.0 GPA by sleeping with her professors is shared, retweeted, and written about online, the fact that it isn’t true is nearly irrelevant. Now, that false impropriety is forever tethered to her name in any cursory online search about this person. Police records can be sealed, whereas Google searches cannot. Employers may not hire people for fear of their digital baggage. Online attacks have the potential to be even more damaging because the private becomes public—forever.

Webcams, the iCloud, and unsecured computers can potentially put an unsuspecting person at risk, exploiting and violating people without their knowledge—until a post or a tweet goes viral. And abundant and easily accessible personal information listed online can allow online followers to transform into real-life perpetrators of sexual violence and rape.

Efforts have been made to improve and clarify the law surrounding consent and rape in California. But, as one reporter put it, “The violence we know exists offline, where women between the ages of 18-24 are more likely to be harassed, stalked, raped and killed by intimate partners, has clearly manifested itself online.” We must also consider how to systematically combat online sexual violence and find a legal recourse for victims of online sexual crime. According to a 2014 Pew study, only 40% of people who experience online harassment take steps to respond to it and only 5% report their problem to law enforcement, a resounding 60% do nothing. Perhaps this is because the methods or options of resolving online harassment are too convoluted or simply ineffective?

While legal scholars and experts are trying to figure out how best to address the act and threat of digital sexual violence (e.g., naked photo hacks, revenge porn, graphic verbal attacks) online communities can continue to self-police. Take YouTube user, Laci Green, who posted a vlog and an open letter about a fellow user, Peppers, who subjected women to street harassment and coerced them into close physical contact (hugging, kissing, touching) as part of a his YouTube “prank” show. Her pressure and her community’s support let members know that certain behaviors will not be tolerated and let YouTube know that these acts are unwanted in their community. The result? Peppers’ video was taken off of YouTube.

In both everyday life and in the physical world, sexual violence is vehicle used to show one’s power over another person, ultimately diminishing and silencing their victim’s agency. While the internet should serve the purposes and democratic ideals of free speech and expression, displays of sexual harassment that are often violent or graphic should not be considered a mere causality in that pursuit of democratic ideals.

Colleen Canniff is graduate of DePaul University, where she studied Psychology, History and Women & Gender Studies and learned that one, perhaps, can have too many hobbies. She is the Executive Assistant to the Director of the Institute for Science, Law and Technology.

Great site! I’m loving it!! Will come back again. I am bookmarking your rss feeds too.