Blog post by Prof. Christi Guerrini, IP Fellow

Prediction by Prof. Edward Lee

On April 28, the Supreme Court heard oral arguments in Nautilus, Inc. v. Biosig Instruments, Inc., a case that will potentially have major implications for patent drafting practices, patent litigation, and businesses. The case centers on the requirement in Section 112 of the Patent Code, which requires patentees to describe their patent claims with sufficient “definiteness.”

Predicting the Winner: Reversal of the Federal Circuit’s Decision

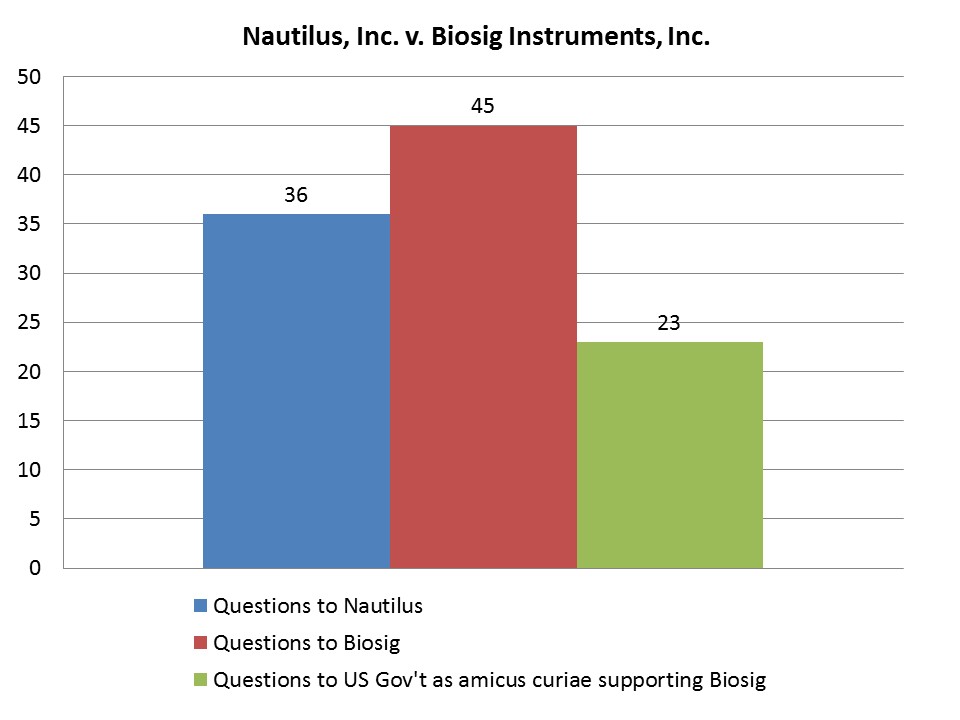

In a prior post, I explained the method by which I am predicting the winners of the case based on counting up the number of questions during oral argument. The side that receives more questions from the Justices typically is on the losing end of the decision. Using that method, the petitioner Nautilus’s side (asking for reversal of the Federal Circuit’s decision) should prevail. The Court asked nearly twice as many questions to the respondent Biosig’s side (including the U.S. government as amicus curiae supporting Biosig). The count was only 36 questions for Nautilus’s side to 68 questions for Biosig’s side.

Figure 1. Number of Questions in the Nautilus v. Biosig Instruments Case

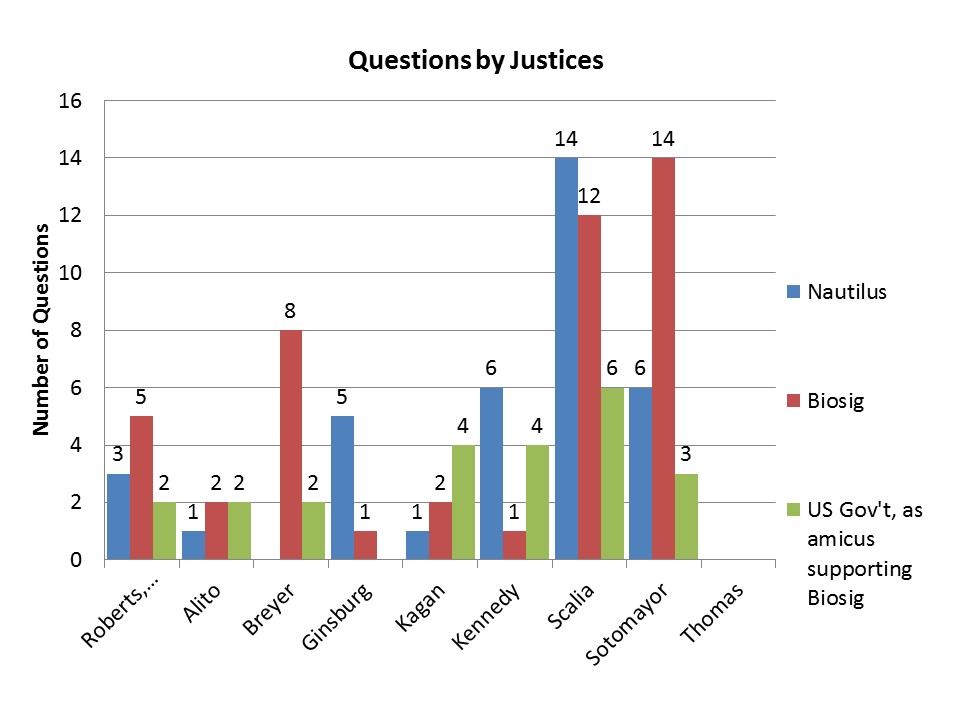

If you look at the Justices’ questions individually, 6 of the Justices asked more questions to Biosig’s side. Only Justices Ginsburg and Kennedy asked more questions to Nautilus’s side, but Kennedy should be discounted because his past questioning defies the statistical pattern used in this method. Thus, based on the above method, a majority of Justices appear to be inclined toward reversing the Federal Circuit’s decision.

Figure 2. Number of Questions by Individual Justices in the Nautilus v. Biosig Instruments Case

Of course, the predicted reversal of the Federal Circuit’s decision does not tell us what test of indefiniteness the Supreme Court will adopt, much less whether Biosig’s patent satisfies that test. But, based on the numbers, it seems very likely the Supreme Court will reject the “insolubly ambiguous” test from the Federal Circuit and reverse the decision below.

Facts

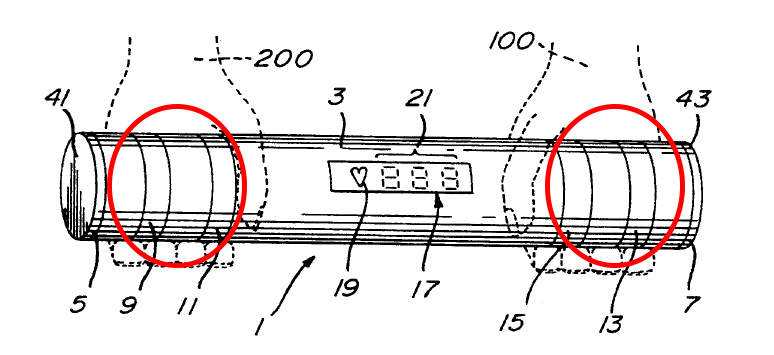

Biosig’s invention is a heart rate monitor that attaches to an exercise machine, such as a treadmill. The monitor is a cylindrical bar with electrodes on it. Someone who is exercising on the machine can grip the bar with both hands, and the electrodes on the bar will detect the user’s heart rate when gripped. The only part of the invention at issue concerns the electrodes. There are two electrodes for each hand. Biosig’s patent requires each pair of electrodes to be “in spaced relationship with each other.” However, the patent does not explicitly identify any limitations or requirements related to the size of the spaced relationship. The patent depicts the pair of electrodes, each “in spaced relationship with each other,” as follows (each electrode pair is circled in red):

Legal Dispute

Biosig sued Nautilus for patent infringement of its heart rate monitor. Nautilus responded by alleging that the patent is invalid for failing to satisfy the definiteness requirement of 35 U.S.C. § 112, which provides that patent claims must “particularly point out and distinctly claim” the subject matter of their inventions. Historically, the Federal Circuit has found patent claims indefinite only when they are not amenable to construction or when that construction is “insolubly ambiguous.” The core issue before the Supreme Court is whether this test is proper.

The trial court construed the “spaced relationship” requirement to mean that there must be a “defined relationship” between the electrodes in each pair, although that relationship does not necessarily need to be equal for the two electrode pairs. Based on this construction, the trial court held the patent indefinite because it says nothing about how big or how small the distance between each electrode pair must be.

The Federal Circuit reversed. The court held that the patent is both amenable to construction and not insolubly ambiguous because limitations on the size of the “spaced relationship” between each pair’s electrodes are “inherent” to the patent. Specifically, a hand must cover each pair of electrodes so the space between each pair cannot be larger than the size of a hand, yet the space cannot be so small that the electrodes basically function as one. The court also understood the space between electrodes to have a function of helping detect electric signals, and it relied on tests performed during litigation demonstrating this functionality to find additional inherent limitations. Finally, the Federal Circuit defended its test for definiteness on grounds that it respects the statutory presumption of validity that all patents carry.

Importance for Business

There is a lot potentially at stake for businesses in this case. If the Court rejects the Federal Circuit test and makes it easier to establish indefiniteness, we are likely to see more patents subject to indefiniteness challenges. We could also see a major change in the way in which patent attorneys draft applications. The current practice of many patent attorneys is to draft patents broadly—and somewhat ambiguously—to ensure that they cover the broadest scope possible, including technologies that arise after the patent has been granted. If the Supreme Court makes indefiniteness easier to prove on a challenge to the validity of the patent, then patent attorneys may have to draft clearer and less broad patent claims (in order to avoid indefiniteness challenges). Narrower and clearer patent claims would, in turn, enable others to predict more reliably how patents will be construed and to avoid infringement. Of course, the hard part is for the Supreme Court to devise a test of indefiniteness that isn’t itself ambiguous, but that instead provides sufficient guidance to courts, businesses, and patentees.

For more, check out this video of Prof. David Schwartz discussing the background of Nautilus v. Biosig and Limelight v. Akamai.

Leave a Reply