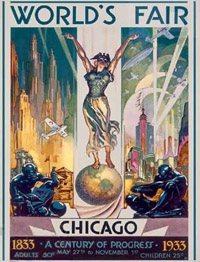

On October 28, 1929, a $10 million dollar bond for the Chicago World’s Fair was issued. The following day, the stock market crashed, bringing the Roaring Twenties to a shuddering halt, and plunging America into the depths of the Great Depression. It was in this economic climate that the Century of Progress International Exposition, the World’s Fair of Chicago, opened in May of 1933 along the shores of Lake Michigan. Thousands of visitors flooded the midway to get a glimpse of the future and forget, if only for a day, about the tempestuous present. “Science Finds, Industry Applies, Man Conforms,” the fair’s motto boasted. Visitors basked in the glow of a giant electric Coca-Cola sign above a rotating lunch counter. Crowds gathered to watch racing champion Harry Hart, “Daredevil of the Race Track,” drive a boxy Chrysler around a 40 degree turn at a terrific 50 miles per hour. The bravest visitors took a spin on the “Skyride,” a slow-moving metal car suspended on cables 628 feet above the ground. With its focus on modern industrial design, new electrical devices, and idealistic interpretations of a healthy and beautiful American future, the Century of Progress International Exposition was a welcome distraction in the gloomy landscape of early 1930s America.

On October 28, 1929, a $10 million dollar bond for the Chicago World’s Fair was issued. The following day, the stock market crashed, bringing the Roaring Twenties to a shuddering halt, and plunging America into the depths of the Great Depression. It was in this economic climate that the Century of Progress International Exposition, the World’s Fair of Chicago, opened in May of 1933 along the shores of Lake Michigan. Thousands of visitors flooded the midway to get a glimpse of the future and forget, if only for a day, about the tempestuous present. “Science Finds, Industry Applies, Man Conforms,” the fair’s motto boasted. Visitors basked in the glow of a giant electric Coca-Cola sign above a rotating lunch counter. Crowds gathered to watch racing champion Harry Hart, “Daredevil of the Race Track,” drive a boxy Chrysler around a 40 degree turn at a terrific 50 miles per hour. The bravest visitors took a spin on the “Skyride,” a slow-moving metal car suspended on cables 628 feet above the ground. With its focus on modern industrial design, new electrical devices, and idealistic interpretations of a healthy and beautiful American future, the Century of Progress International Exposition was a welcome distraction in the gloomy landscape of early 1930s America.

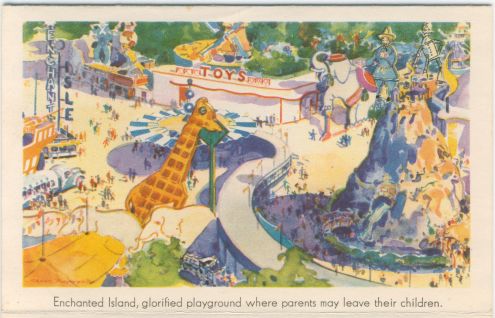

Dedication ceremonies took place in late spring of 1933. On the afternoon of May 6, Mrs. Lennox Lohr broke “a great big bottle of milk over that grand pink confection known as Magic Mountain.” The dedication signified the opening of the Enchanted Island, a section of the fair situated between a lagoon and Lake Michigan, filled to the brim with entertainment for children. Near the Magic Mountain, which doubled as a large slide, was a giant Radio Flyer wagon, a mechanical zoo, a tiny “fairy castle”, a miniature theater featuring plays such as Peter Pan and Cinderella, all encircled by a child-sized locomotive for little passengers.

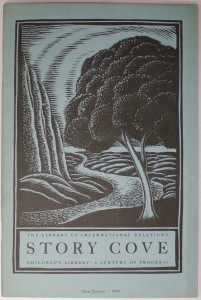

Weary parents checked their children into the Enchanted Island for any amount of time from an hour to an entire day. Near the entrance, where youngsters were released to roam free in this mini-Utopia, boys from the Francis Parker School walked back and forth, shifting uncomfortably under the weight of their sandwich boards, which displayed the messages “Follow the Shore to Story Cove and Hear Tales of Many Lands” and “Rest a While at Story Cove with Adventurous Heroes from the Land of Books.” Beyond the roar of car engines, screams of roller coaster riders, and the noise of the crowds shuffling through hundreds of exhibits under the hot sun, there existed a small, quiet room filled with child-sized tables and chairs. The room, known as the Story Cove, was also home to a collection of nearly 1600 children’s books in 17 languages from 57 countries around the world. Sheltered from the sun and insulated from the electric hum of progress booming all around, cooled by the breeze off Lake Michigan, children sat and read from a new library of stories by authors outside the canon of popular American children’s literature.

The Story Cove was a project of the Library of International Relations, a small Chicago library with a mission of increasing international understanding, which would one day become a part of Chicago-Kent. Organized in 1932 by Eloise ReQua with funds from the Carnegie Foundation and the Woodrow Wilson Foundation, the Library’s first home was a single room provided by the John Crerar Library at the corner of Randolph and Michigan Avenue. The LIR was established as an open-shelf reference collection dealing with international affairs, with a focus on twentieth century events, especially World War I. Documents of the International Labor Office, the Permanent Court of International Justice, and the League of Nations were preserved and made available to the public by Ms. ReQua and fellow librarians. In the spring of 1933, the children’s collection was created with the Century of Progress in mind. “International relations,” Ms. ReQua told the Chicago Tribune, “may seem far removed from a child’s life, but the story book friends of foreign lands give children an understanding and sympathy with other ways and other aspirations, and such an understanding may prove a balance wheel in later years.” For over a year, librarians sent hundreds of letters to publishers around the world requesting books for the Story Cove, so that American children could read a variety of titles, such as The Fat of the Cat and Other Stories by Gottfried Keller of Switzerland, In the Days of Giants by Abbie Farwell Brown from Scandinavia, and Boy of the Desert by Eunice Strong Tietjens of North Africa. They also gathered a small group of Newbery award-winning books, which were hand bound by famous bookbinder Ernst Hertzberg. Their vision was for a collection which would give a wider international view of children’s literature than the average American child was likely to have. They were destined to succeed.

Children reading in the Story Cove reading room (image from On the Shelves of the Story Cove, 1934).

When its doors opened to the broader public on May 27, 1933, the Story Cove became an instant favorite. English vice consul Lewis Bernays visited the Story Cove to join in a birthday celebration for King George V. Visiting children from Scotland and Ireland sang traditional songs and performed “the Highland fling.” Children learned Native American stick games and made decorations for the national holidays observed in other lands. Singers, actors, and writers visited the Story Cove and gave special storytelling performances, some of which were broadcast on WGN Radio. Each day featured readings and activities based on international themes, with special storytelling guests on the weekends. The main attraction was, of course, the children’s library, and the many interesting books it held. The Chicago Tribune reported that “[f]air authorities had to enforce strict regulations to keep the little reading room for boys and girls instead of their mothers and fathers.”

On the Shelves of the Story Cove, 1934. Records of the Library of International Relations, AC001, IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law Archives.

In November of 1933, the Fair closed for the winter, but re-opened in May of 1934. The fair closed permanently in the following November, but not before paying its entire debt. In its two year run, the Century of Progress International Exposition had attracted over 48 million visitors and become the first international fair in American history to pay for itself. At the end of 1934, the books of the Story Cove were packed away for storage, the LIR librarians taking a break from the project to re-focus on the Library’s permanent collections. Finally, in May of 1935, the Chicago Tribune reported that “[b]oys and girls who spent long, happy hours the last two summers in the Story Cove at A Century of Progress, now only a memory, will dance with glee this morning when their mothers tell them that again they are to enjoy their little library.” The Chicago chapter of the Red Cross had agreed to set up the children’s reading room in a corner of the Red Cross headquarters at 616 Michigan Avenue, where it became known as the Junior Red Cross Story Cove. In 1983, the Library of International Relations was acquired by the Chicago-Kent College of Law. Today, all that remains of the Story Cove collection of the LIR are archival copies of On the Shelves of the Story Cove, a list of the books featured in the original Story Cove in 1934, produced by LIR librarians in response to the flood of requests from parents and teachers for more information on the titles their children had enjoyed during those two magical summers.

The 1933 Century of Progress International Exposition became known as a “break in the clouds” for many people struggling with the darkness of the Great Depression. Its acknowledgment of a changing world and focus on a brighter, happier future became a beacon around which millions could stand in awe and enjoyment. The creators of the Story Cove extended that sense of wonder and hope for the future by creating a place for children to learn about the world at large, about different cultures and experiences outside of their own. The foreword to On the Shelves of the Story Cove expresses their mission thusly:

“With all the world we wish for the new child, eyes that will see, ears that will hear, hands that will shape the raw materials of the earth into bits of beauty, hearts that will beat with the throbbing currents of the universe…long life with dreams.”

Resources:

Bennett, James O’Donnell. “Library Solves Queries On Far Parts Of Globe.” Chicago Tribune, 2 Sept. 1934: 5.

Cass, Judith. “Fair Trustees to Arrange Today for Enchanted Island Opening.” Chicago Tribune, 27 Apr. 1933: 13.

Cass, Judith. “Story Cove for Children at Fair.” Chicago Tribune, 26 May 1933: 21.

Cass, Judith. “World’s Fair Story Cove to Be Reopened.” Chicago Tribune, 16 May 1935: 19.

On the Shelves of the Story Cove, Records of the Library of International Relations, AC001, Box 13. IIT Chicago-Kent College of Law Archives, Chicago, Illinois.

What a great story. I had no idea of the timing of the market crash and the opening of the world fair.