Earlier this semester, Professor Nancy Marder and Professor Tomoko Ichikawa organized a collaborative faculty workshop for Chicago-Kent College of Law and IIT’s Institute of Design. The workshop considered the problem of jury instructions in the legal field and how design strategies could be applied to work towards effective solutions.

Speaking at the Faculty Workshop for Chicago-Kent College of Law and the Institute of Design, these faculty members discussed issues with jury instructions and strategies each discipline might bring to a problem like this one.

Professor Marder noted the purpose, use, and specific problems with jury instructions. She also described methods that have been used to try to solve those problems and some of the major challenges to enacting changes.

Professor Tomoko Ichikawa shared processes that the design school uses to address this type of issue. Faculty from both schools offered questions and suggestions in an interactive portion that lead to a discussion of what larger issues might need to be taken into account and how formal design approaches could be misused if not well understood.

Jury Instructions

Goals & Use

Written jury instructions explain the law jury members are expected to follow when deciding the outcome of a case. Often, these instructions are read aloud by the judge to the jury at the end of the trial, before deliberations begin. They may be tailored to a specific case after discussion between the judge and the lawyers.

Often, jury instructions for a given trial can take a minimum of 30 minutes to read aloud. In most courtrooms, juries cannot take notes and are not given a written copy of the instructions.

Problems

The language of jury instructions is written by committees. The instructions are usually not designed for ordinary readers but for legal professionals. Usually, when writing instructions, these committees of judges or judges and lawyers stick close to the original – often obtuse – language of statutes and case law. Professor Marder noted that 35 years of empirical studies have proven that juries struggle to comprehend these instructions.

The format of the presentation is another major problem. It is very hard for juries to retain and absorb information that’s only presented orally and in long lectures, particularly if they can’t take notes. Younger jury members particularly struggle with these lectures.

Proposed solutions

In California and Arizona, it took 6-8 years for special committees to rewrite their jury instructions in plain language, sticking to a 6th-8th grade reading level. Other states or individual judges have worked on smaller scale solutions, such as providing a copy of the instructions, letting jurors take notes, or using a PowerPoint to highlight the content.

Professor Marder called judges with PowerPoint “maverick judges” and suggested tools –such as recordings of the instructions that jurors could take into the jury room — that might be even more helpful. She highlighted other proposals, from letting jurors ask questions before deliberating to providing juries the explanatory headnotes from the written jury instructions.

Challenges:

There are several fundamental obstacles to making headway with any proposed solutions:

- The legal field changes very slowly

- Jurors don’t usually have a chance to give feedback on their experiences, so there isn’t a lot of information to act upon

- Changes would need to be approved by officials like state chief justices – and this approval is not easy to obtain

Design Strategies:

Professor Ichikawa noted that she was not a U.S. citizen so she has not had any personal experience with our jury system. But because the purpose of the workshop was to demonstrate how the ID process analyzes problems like this one, her inexperience should not affect the value of her analysis.

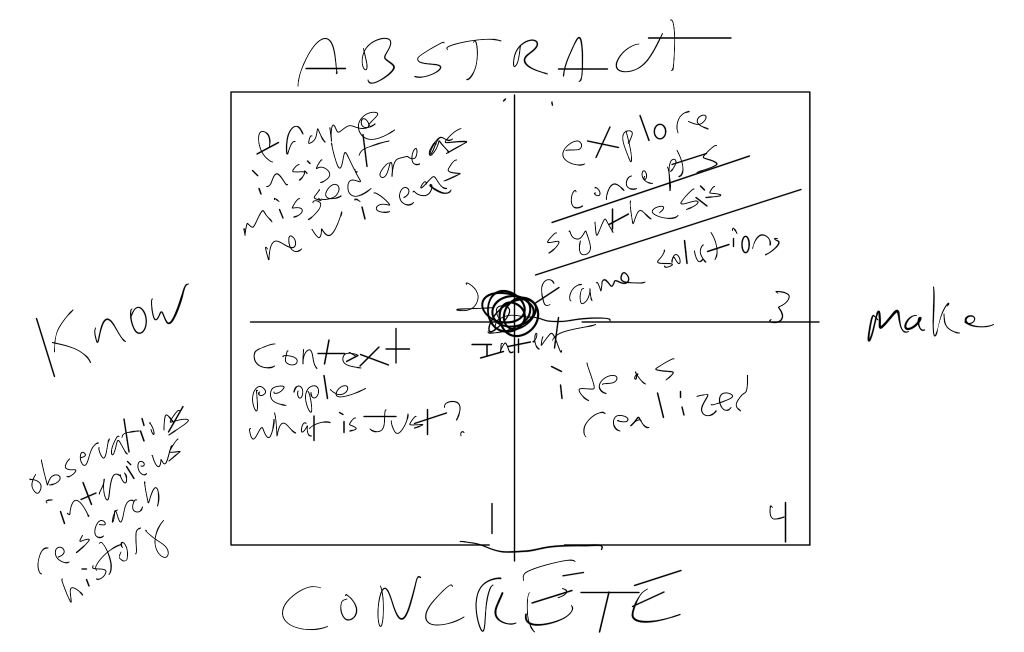

Quadrant Diagram

First, Professor Ichikawa drew a quadrant diagram with a horizontal axis moving from “know” to “make” and a vertical axis moving from “real/concrete” to “abstract”. Starting at the center – labeled “intent” – she moved clockwise around the diagram, defining the design process.

The first stage, observation, defines the context of the problem and might include conducting interviews, studying trends, and researching history. The second stage, insights, involves evaluating data and opportunities. The third stage, synthesis, requires trying out concepts that might be used in the next stage. The final stage enacts concrete solutions.

Professor Ichikawa then considered issues with the systems and interfaces inherent within jury instructions. Jury instructions could be seen as an interface, but jury deliberation is part of a larger system that needs further evaluation.

Systems affecting jurors:

Aspirations/goals

Aspirations/goals- Routines/rituals

- Activities

- Networks: social, professional, family

- Anxieties

- Values/beliefs

Interfaces affecting jurors:

- Products

- Services

- Experiences

- Processes

Group Discussion:

Faculty members from both ID and the Law School then considered the problem Professor Marder presented within the framework provided by Professor Ichikawa.

Q: Why not build on the California and Arizona models?

A: Lack of political will, need leadership, especially from chief justice in each state.

Q: Who would need to be involved to make progress on this issue?

A: Legal committees, judiciary, public, lawyers

Q: Could there be a digital entry point to encourage jury participation?

A: We already have issues with jurors posting on social media when they’re not supposed to, this is a delicate issue.

Q: If the issue is memory, how could you increase information persistence?

A: Signs on the jury room walls, contextual help “in situ” for terminology – legal glossaries in the room vs. people using their own phones. Creating a closed, internal research system could address some concerns about allowing technology into the jury deliberation process.

Q: Isn’t the larger issue civic engagement and how much we value the experience of being on a jury?

A: Small things, like having vending machines near where jurors have to wait, could improve the immediate experience.

Q: Are there studies on the types of questions that juries ask?

A: Studies have found that 80% of inquiries about being on a jury are people learning how NOT to be jurors, which definitely affects the impact of who serves on juries.

Design Concerns

Design faculty pointed out there’s often a perception that a problem like this could be fixed with a single well-designed product, rather than incorporating some of these design questions and strategies into the system to allow for continuing improvement.

Prototyping Process

The prototyping process moves in a cycle:

Entice > Enter > Engage > Exit > Extend (and repeat)

Shared personal stories about jury duty or perceptions from TV probably govern the “entice/enter” stage. Jury instructions do not make for good TV, so they aren’t part of people’s expectations. They may be an attempt to engage, but the reaction of juries when they leave and discuss their experiences will more likely provide useful feedback for the current system.

Evaluating the experience would mean looking at personal costs, from time off work or for childcare to parking, personal stress in the waiting process and more.

If the legal infrastructure included design approaches, they would think of it more as a communication/engagement system that needs a holistic approach because it is complex and dynamic.

Conclusion

Issues with jury instructions cannot be fixed in a single workshop, but the content and format helped faculties from diverse academic programs learn how their specific fields of studies might interact and provided questions for future discussions.