The Supreme Court heard oral argument in two cases on Monday, including an important First Amendment case involving threats on Facebook. I’m predicting the winners of the Supreme Court cases based on the number of questions asked during oral argument. For more about this method, see my post on last Term’s Aereo case.

Perez v. Mortgage Bankers Ass’n asks whether a federal agency must engage in notice-and-comment rulemaking pursuant to the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) before it can significantly alter an interpretive rule that articulates an interpretation of an agency regulation.

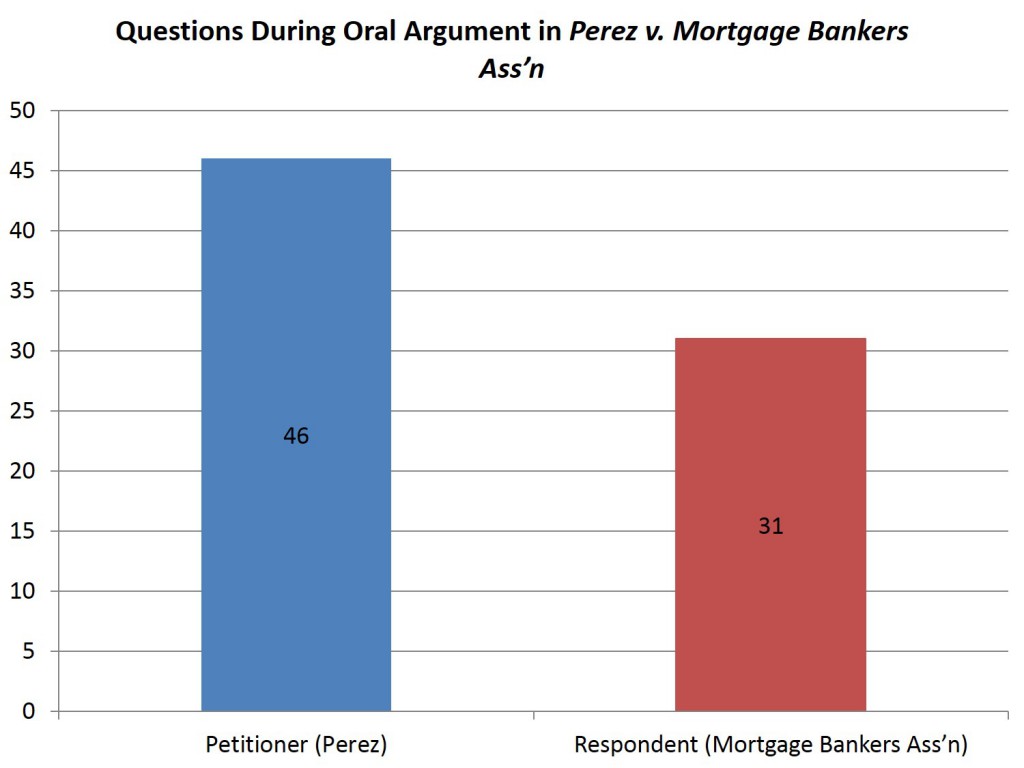

This case is easy to predict. The Court asked the Petitioner (Solicitor General arguing for Secretary of Labor Perez) 46 questions, 15 more than asked of the Respondent (Mortgage Bankers Ass’n). The large question disparity strongly suggests a win for the Respondent, who argued for an affirmance of the D.C. Circuit opinion that invalidated the Department of Labor’s 2010 interpretative rule (i.e., that mortgage-loan officers are not exempt from the requirement for overtime pay) because the agency failed to subject its change in position to APA notice-and-comment rulemaking.

UPDATE: After receiving a number of comments from observers who thought the oral argument showed the Court was clearly siding with the Petitioner (contrary to my prediction), I went back over the question count per Justice. I still don’t see a victory for the Petitioner. Six Justices asked the Petitioner more questions by a pretty decent margin: Roberts (+7), Scalia (+6), Kennedy (+4), Breyer (+3), Alito (+4), and Sotomayor (+4). Also, the Justices asked 8 questions during the Petitioner’s rebuttal, which is an unusually high number.

Only Justices Ginsburg (+3) and Kagan (+10) asked the Respondent more questions. Justice Kagan dominated the questioning of the Respondent with over 30% of the questions asked. Based on some observers’ comments, apparently the Respondent’s lawyer may not have handled Justice Kagan’s questions that well (which might explain why Justice Kagan asked numerous follow-up questions). If the Court does side with the Petitioner, I would be surprised. Of course, the predictive value of question counting has its limits. This could be a case in which the question count masks a different dynamic. For example, if the Petitioner does prevail, the high number of questions to the Petitioner could reveal the Court’s wrestling with the precise way to craft its ruling for the Petitioner, and the low number of questions to the Respondent could reveal the Court simply “not buying” the Respondent’s argument to engage it. We’ll have to wait and see. But I’m sticking with my original prediction based on the question counting method.

Figure 1.

The second case, Elonis v. U.S., asks (1) whether, consistent with the First Amendment and Virginia v. Black, conviction of threatening another person under 18 U.S.C. § 875(c) requires proof of the defendant’s subjective intent to threaten, as required by the Ninth Circuit and the supreme courts of Massachusetts, Rhode Island, and Vermont; or whether it is enough to show that a “reasonable person” would regard the statement as threatening, as held by other federal courts of appeals and state courts of last resort; and (2) whether, as a matter of statutory interpretation, conviction of threatening another person under 18 U.S.C. § 875(c) requires proof of the defendant’s subjective intent to threaten.

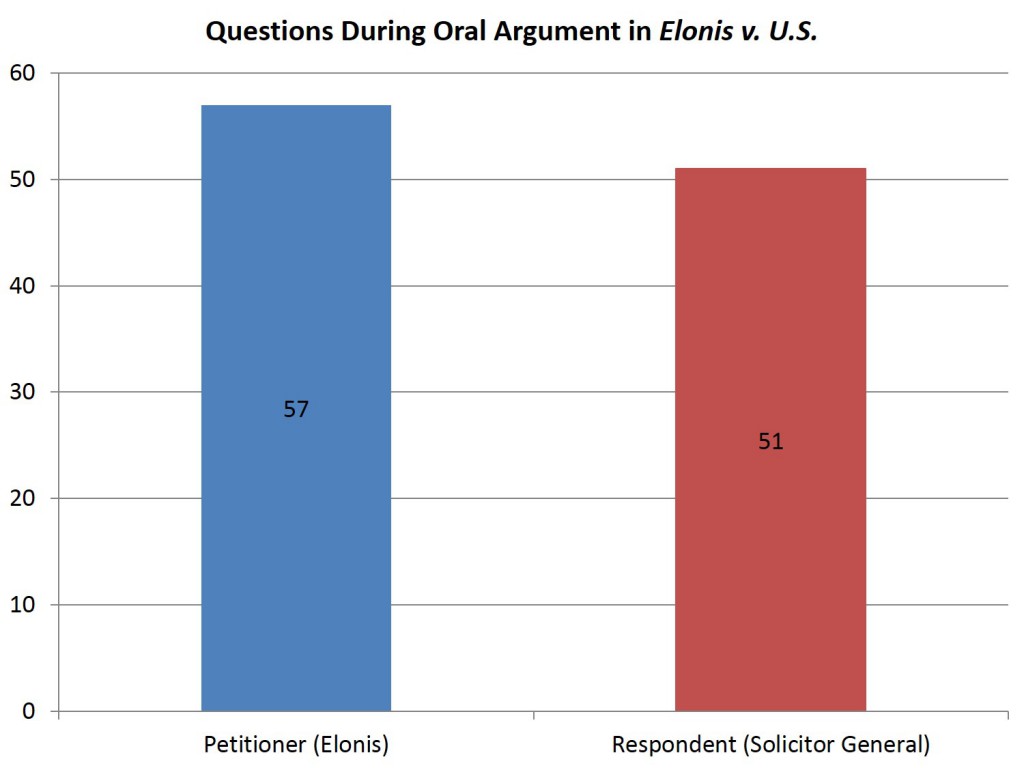

This case is a close call. Although the Court asked the Petitioner (Elonis) 6 more questions (see Figure 2), the overall question count for the Petitioner is somewhat inflated by Justice Scalia’s 19 questions, an unusually high number for a Justice to ask one party. Looking at the questions asked by Justice tells a somewhat different story. Four Justices (Scalia (+16), Ginsburg (+1), Alito (+7), Kagan (+2)) asked the Petitioner more questions, and four Justices (Roberts (+6), Kennedy (+3), Breyer (+5), Sotomayor (+6)) asked the Respondent more questions. The alignment of Justices defies the typical conservative-liberal Justice pattern in close cases.

So who wins? It is very hard to predict based on these numbers. Moreover, given the two questions presented for review, it is certainly possible that both sides could win on some issues. Therefore, my confidence level is not high, but if I had to pick a winner, I would give a slight nod to the Petitioner (Elonis).

Three Justices asked at least 5 fewer questions to the Petitioner, whereas only two Justices asked at least 5 fewer questions to the Respondent. In other words, even though the Justices split 4-4 in terms of which side they asked fewer questions (Justice Thomas asked no questions), more Justices asked the Petitioner far fewer questions (by a differential of at least 5 questions). Justices Ginsburg and Kagan asked the Petitioner only one and two more questions, respectively, a differential that does not provide much basis to suggest they are leaning to the Respondent’s side. I also find significant Chief Justice Roberts’ 6 fewer questions to the Respondent, a differential that does suggest a leaning to that side. A possible majority for Elonis could be Chief Justice Roberts, and Justices Kennedy, Ginsburg, Breyer, and Sotomayor, plus possibly Kagan. On the other hand, Justice Kennedy is harder to predict based on his question count, so the decision may well end up a 5-4 decision.

Figure 2.

Really on Perez? I though the respondent did a horrible job answering questions. Maybe the justices just had a hard time understanding her, or vice versa. In fact, justice Kagan was visible annoyed with the attorney’s inability to concede kagan’s point.

Thanks for your comment, Jen. I’ve heard others who had similar views from the oral argument–i.e., the Court was siding with the Petitioner.

Using the question counting method, I don’t actually evaluate the substance of the questions (whether hostile, friendly, or too hard to decipher). I may well be wrong on this prediction, given what you and others have said.