Blog post by Prof. Christi Guerrini, IP Fellow

Prediction by Prof. Edward Lee

On April 30, the Supreme Court heard oral argument in Limelight Networks v. Akamai Technologies, a case involving the thorny issue of “divided” patent infringement—specifically, whether a defendant may be held liable for inducing patent infringement under 35 U.S.C. § 271(b) even though no one has committed direct infringement under Section 271(a). The Court’s decision is likely to have important implications for developers of distributed systems and method innovations that are typically executed by multiple independent persons. For example, patents on Internet services and business methods may involve some steps of the patented method that are performed by the technology company and other steps performed by customers.

Predicting the Winner: A Win for Akamai?

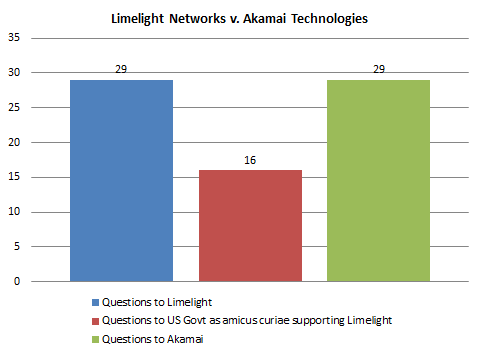

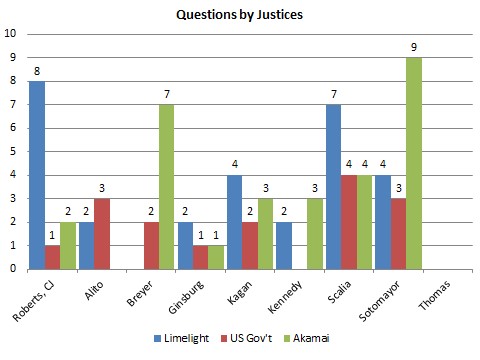

In a prior post, I explained the method by which I am predicting the winners of the case based on counting up the number of questions during oral argument. The side that receives more questions from the Justices typically is on the losing end of the decision. Using that method, Akamai might get a slight edge to win the case. As depicted in Figures 1 and 2 below, 5 justices asked Limelight’s attorney more questions, and, when coupled with the questions to the U.S. government (as amicus curiae supporting Limelight’s side), the Justices asked 16 more questions to Limelight’s side, 45 questions to only 29 questions to Akamai. Those numbers suggest a win for Akamai based on this method.

However, I am not too confident in this prediction. The Justices did in fact ask the same number of questions to both parties (29)—which suggests a closer call. As I’ve noted in the prior post, the presence of an attorney for a non-party (an amicus) may skew the numbers somewhat if the Justices feel obliged to ask every attorney some questions. Plus, the U.S. government’s position may confound the conventional analysis of the number of questions. In a different case just decided this week, Octane Fitness, LLC v. ICON Health & Fitness, Inc., the number of questions was quite similar to this case, but it defied the pattern described above. In Octane, there was an even split of questions between the parties (31), plus a differential of 51 questions for petitioner’s side (adding in the U.S. government as amicus curiae) to 31 questions for the respondent’s side. But the Supreme Court ultimately decided in favor of the petitioner, despite its side receiving the greater number of questions. The Octane case suggests that the questions in Limelight may defy the conventional pattern—which would bode well for Limelight.

Figure 1. Number of Questions in Limelight Networks v. Akamai Technologies

Figure 2. Number of Questions by Individual Justices in Limelight Networks v. Akamai Technologies

Facts

Akamai Technologies owns the patent at issue, which covers a method for the efficient delivery of content over the Internet. The dispute centers on the following steps of the method: (1) the URLs of certain elements or objects featured on a content provider’s website are modified, or “tagged,” to link to a system of servers placed at various geographical locations, and (2) the tagged objects are then replicated on the servers. Limelight, a competitor, maintains a network of servers on which it similarly places tagged objects featured on the websites of its customers. It does not, however, itself tag these objects. Rather, the customers themselves can choose to tag the objects they select per Limelight’s instructions.

Legal Dispute

The issue before the U.S. Supreme Court is whether a defendant may be held liable for inducing patent infringement where no entity is liable for direct patent infringement. In the case below, Akamai sued Limelight for patent infringement. The traditional rule of patent law is that an entity cannot be liable for directly infringing a claimed method under 35 U.S.C. § 271(a) unless it performs every step of the method. The entity also cannot be liable for inducing infringement under 35 U.S.C. § 271(b) if the claim has not been directly infringed. In other words, there can be no induced infringement if there is no direct infringement.

Following a jury trial in which Limelight was found liable for direct infringement, the trial court granted Limelight’s motion for judgment as a matter of law. Applying a theory of divided direct infringement, the court held that Limelight did not sufficiently direct or control the actions of its customers and so could not be held liable for direct infringement. On appeal, a 3-judge panel of the Federal Circuit upheld the trial court’s ruling. Elaborating on the theory of divided direct infringement, it held that there can be no liability under this theory unless there is an agency relationship between the parties who jointly performed the steps of a method claim or one party is contractually obligated to another party to perform the steps.

However, after a different panel of the Federal Circuit affirmed summary judgment of noninfringement in McKesson Technologies v. Epic Systems Corp, the Federal Circuit granted both Akamai’s and McKesson’s petitions for rehearing and the en banc court heard both cases on the same date. In a 6-5 per curiam decision addressing both cases, the Federal Circuit focused solely on whether an entity can be liable for inducing infringement of a method claim if no single entity performed all of the steps. The majority held that all of the steps of a claimed method must be performed in order to find induced infringement, but not necessarily by the same entity. In so holding, the court overruled its prior approach requiring a single entity to be liable for direct infringement in order to prove a claim of induced infringement. The court determined that the prerequisite to a finding of induced infringement is performance of the steps of a claimed method, either by a single entity or multiple entities collectively performing all of the steps.

The court explained: “A party who performs some of the steps itself and induces another to perform the remaining steps that constitute infringement has precisely the same impact on the patentee as a party who induces a single person to carry out all of the steps.” The Federal Circuit overruled its prior approach that required that “the accused infringer directs or controls the actions of the party or parties that are performing the claimed steps,” in order for the joint activity of the defendant and third parties to be aggregated together to establish direct infringement. Thus, because Limelight itself and its customers were alleged to have collectively performed all of the steps of the claimed method (even though none performed all the steps individually), the prerequisite could be satisfied. Judges Newman and Linn separately dissented.

The court remanded the case to allow Akamai to proceed against Limelight on a theory of induced infringement. “Limelight would be liable for inducing infringement if the patentee could show that (1) Limelight knew of Akamai’s patent, (2) it performed all but one of the steps of the method claimed in the patent, (3) it induced the content providers to perform the final step of the claimed method, and (4) the content providers in fact performed that final step.” The Supreme Court agreed to review the Federal Circuit’s en banc decision.

Importance for Business

The Supreme Court’s decision is likely to have important implications for businesses, especially in industries such as financial services, Internet, and telecommunications that are focused on developing systems technologies, some of which by their nature cannot be performed by single entities. If the Court agrees with the Federal Circuit that an act of induced infringement does not require the underlying act of direct infringement to be performed by a single entity and that an alleged inducer’s own acts can count with acts of its customers to establish all the steps of the patented method for direct infringement (even though the customers did not act under the control of the alleged inducer), we should expect to see more patent lawsuits being filed. We should also expect to see more innovators seek—and patent attorneys draft—broader, or “bigger,” method and systems patents since they will be less concerned with trying to avoid the traditional single-entity rule of direct infringement. However, if the Supreme Court rejects the Federal Circuit’s broad approach to divided infringement, the Court could discourage patent lawsuits that are based on extravagant theories of induced infringement. Some patent experts fear that patent trolls can more easily assert induced infringement claims under the Federal Circuit’s ruling. On the other hand, the Supreme Court still must figure out how divided infringement claims should be adjudicated. If the requirements of proof are too high, then crafty defendants can avoid infringement claims on method patents by effectively outsourcing a key step of the method to their customers.

For more, check out this video of Prof. David Schwartz discussing the background of Nautilus v. Biosig and Limelight v. Akamai.

Leave a Reply